This is an ongoing series delving into which smartphone OS is for you? Already an iPhone user? Obsessed with your BlackBerry? Need your Android fix? Read on for a taste of them all, and maybe you’ll learn whether…

Is Android Right For You?

We’ve have already looked at Windows Phone 7, and according to the latest statistics, most Canadians figured out a long time ago that iOS is right for them (coming in a future column) but Android seems to be the curious choice for mainstream consumers these days.

It is ubiquitous. From the $150 LG Optimus Chic to the $599 Motorola Atrix (to $799 Xoom tablet), and hundreds of devices in between, you can’t seem to escape its diminutive robot interior. Since launching in 2008 it has proliferated to 350,000 activations per day on almost every carrier around the world. Its primary backing manufacturers, HTC, Samsung and Motorola especially, have benefited from its open source roots, and adroitly add features to the stock experience to differentiate from the myriad choices out there.

But Android is still seen primarily as a competitor to iPhone, and to the “walled garden” of Apple’s App Store. Created and backed by Google, it has been deemed the open alternative, a platform where ideas, customization and, most importantly, choice are both welcomed by its fans and vilified by its detractors. No one can deny that Google has created a virtual monster, and like it or not, you’re going to see at least one Android device beckoning at you when you seek out your next smartphone. Is Android right for you? Read on to find out.

Similarities:

Most smartphone operating systems rely on an icon-based home screen workflow, where a limited amount of essential information is made available to the user, and by downloading applications from its requisite marketplace, more features are made available. iOS has perfected this model.

Android makes use of this idea, but expands and complicates it with the addition to the home screen of widgets and a permanent notification bar. Indeed, without even opening an application, a great deal of information can be gleaned, from weather to stocks to tweets.

The permanent expandable notification bar at the top of the screen is also a huge advantage to the notification systems in other mobile platforms. It means that, unlike the current iOS system, notifications can be stacked and actioned at the users’ convenience. But it’s not exactly pretty: each notification, though uniform in its top-down, boxy presentation, is designed by the developer of the app. webOS done a lot to improve its notification system in its 2.1 version, and Android has picked up some of that for 3.0 Honeycomb, where the notifications are at the bottom of the screen as individual little icons that expand once touched. Very intuitive.

Differences:

Android is slightly different in its makeup than most of the other mobile platforms out there in that its component parts are built primarily on heavily customized, yet off-the-shelf Linux parts. Due to its open source nature, Google agrees to open-source the code of each new version after it is finalized (though it has delayed the release of Honeycomb for compatibility reasons). This allows anyone to compile the code and attempt to run it either on a device, or emulated on their computer. It also allows for a very active developer community.

While HP’s webOS has a thriving developer community, it is significantly smaller than its Android equivalent for a number of reasons, but mainly because there are far fewer handsets out there.

To some extent, Android’s biggest advantage and its greatest liability is the quasi-legal status in which many of these developers’ custom ROMs exist. I will touch on this later.

Touch-love:

Android was designed for scalability. It has been installed successfully on hundreds of handsets at different resolutions and screen technologies. From the 2.8” screens of the Motorola Charm to the massive 7” screen of the Samsung Galaxy Tab, it scales very well. It also allows for touch and hardware keyboards alike in any number of configurations.

But mainly Android was designed to be used with capacitive touch screens at 3” and above, and over the years many improvements have been made to its multitouch capabilities. If you are concerned that by moving to Android you will lose the fluid browsing and pinch-to-zooming of your iOS or webOS experience, you don’t have to worry. In fact, technically, Android is as capable as any mobile OS. If an app of feature does not exist that does on another platform, you can rest assured that someone will cook up a version of their own.

Half-baked:

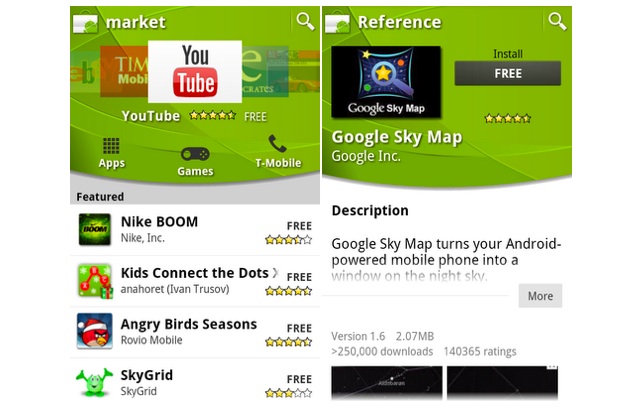

At times, the problems with Android stem from that previous sentence. Due to the largely un-moderated nature of the platform, there is no limit to what you may code, and load, onto your device. Sideloading, or installing apps from outside the official Android Marketplace, is not only possible but encouraged. That leaves all Android phones vulnerable to malicious code. Even apps installed from the Marketplace do not have to be approved by Google, and enforcement is only done when complaints are received. Apps updates are pushed immediately, which is nice, but because the code isn’t checked for bugs or API adherence the prevalence of buggy code increases.

So, with Android you have a choice. It can be quite rewarding to discover a polished, unique, capable app from a small developer in the Android Market. But there is equal chance of installing a dud, a clone of a popular iOS app that mimics nothing but the name, or worse, an app with malicious code. By default, Android does not enable sideloading apps, which provides some protection. (AT&T has gone one step further and disallowed the process altogether.)

Where the App Store Comes for Free:

iOS has a very closed, controlled ecosystem. That also engenders a sense of security and reliability when buying an app. Android’s ecosystem is more vulnerable to piracy; it doesn’t take a jailbreak to download a paid app in .apk format off a forum.

That also means that the Android Marketplace, at least in terms of revenue for developers, has been largely considered a failure. Though the number of apps has grown exponentially, approaching the 300,000+ of the iOS App Store, the vast majority of downloads are free and ad-supported. They are aided by the proliferation of Google’s AdMob network; Rovio, makers of Angry Birds, boasted recently that they are earning $1 million every month in ad revenue through its Android app.

Amazon have launched a competitor to the Android Marketplace, in which all apps must be approved by their quality control department. Though most apps will presumably be available in both, Amazon is attempting to inject some legitimacy to the process. The fact that alternate app stores exist in Android is, in general, a huge divergence from most other mobile platforms.

Is Android for me?

Multitasking:

Android has matured to the point where, unless you run bad code, it is relatively stable. Apps do occasionally crash without warning, and there are tons of design inconsistencies between apps. Very few apps adhere to the design standards preached by Google themselves (see the official Twitter app, or Winamp, for examples of those that do), but those that do are attractive and functional.

Multitasking in Android is arguably better than in iOS, since apps can be stored as services that exist in the background (of course using up RAM and system resources, but are more efficient than if they are left in the foreground), allowing for music and location-aware apps to work behind the scenes, but also to have pervasive widgets and notifications. Push services work, too, by having the app stored as a service. If developers are smart, and use the correct APIs, background apps do not have to drain battery life. As most Android users know, however, that is not the case. Something to keep in mind, though on the plus side, most devices have replaceable batteries.

Skins:

Manufacturers also skin their versions of Android to add value. HTC, for example, created its Sense UI as an overlay for Windows Mobile 6.0 and has updated it for Android with great success. Taking many of the underlying features of the OS and tweaking or improving on them, its distinctive visual style and impressive feature list, along with the superior hardware to accompany it, has brought the company much success. Similarly, Motorola and Samsung, along with many other smaller OEMs, have attempted to differentiate themselves through their skins and value-add apps. Except for HTC, most arguably fail.

But it certainly begs the question of whether Android can stand on its own. Similar questions have been made about iOS: could it be as successful as it has been without the App Store? Both platforms come out of the box with certain first-party apps that provide limited access to news, weather, stocks, along with email and messaging capabilities. BlackBerry built their business around those core features: they didn’t introduce an app store until 2009.

Stock Android is pretty ugly. Gingerbread, Android 2.3 improved the situation slightly, but compared to iOS there are menus upon context menus, inconsistent design choices and generally unflattering colour palettes. Google doesn’t sweat the small stuff: they are into big picture ideas, and take a long time to get the design part down. For most people, this won’t be an issue, but coming from iOS or webOS, it’s a stark contrast of function over form.

Power under the hood:

By eschewing many of the design principles and consistencies so often described when praising iOS, Android has managed to stay quite light on its feet. Sure, circa 2009 the platform was clunky and slow, but we’ve reached a point where powerful hardware has married optimized software and we’re left with scorching performers like the Motorola Atrix and Samsung Galaxy S.

Hardware acceleration and powerful GPUs have finally made Android a viable gaming platform. In fact, Sony Ericsson is soon releasing the Xperia Play, an Android device with a slide-out gaming panel. Finally, too, the best iOS games are coming to the platform.

Open source community management:

You’ve likely heard the term ‘jailbreak’ to describe breaking the underlying protection of an iPhone and allowing non-market apps to be installed, as well as tweaks to the interface. Android has a few layers of jailbreak, and the first begins with ‘root’, allowing read-write access to the core Linux directories behind the scenes. Changes can then be made to the filesystem, allowing for some very neat enhancements to the experience.

Going one step further, once root has been achieved there are also terms like ‘recovery’, ‘bootloader’ and ‘ROM’ to consider. Suffice it to say, Android chefs are always cooking up enhanced versions of the ROM that comes loaded up standard on your phone. Communities like CyanogenMOD have unified the experience, allowing for the same powerful ROM to be loaded on nearly 30 different devices. The process has been refined to business-like efficiency, and it wouldn’t surprise me if the main players are offered jobs by the very companies that mean to keep them out.

Hardware variety:

It’s hard to keep up with the influx of Android devices coming out these days, and some of the hardware is stunning. From the sleek plastic of Samsung to the unified aluminum shell of HTC, there are myriad devices for every need.

Due to the low-cost nature of the code (it’s not free since Google requires OEMs to pay for its first-party apps) there has been an influx of lower-cost Android devices into the market. Such is the reason for the extreme proliferation of the platform, but also introduces questionable quality into the market. A good example of a well-made product that provides mid-range performance as a low price point would be the LG Optimus line, which is available in some variety on most carriers worldwide.

Forced Closure:

As mentioned earlier, Android apps have become more stable over the years, but to use the platform necessitates some amount of patience. There are still occasional random crashes, reboots and unexplained events that can leave you flummoxed and frustrated.

As a result, Android isn’t typically as ‘easy’ to use as iOS or webOS, but with some time its quirks become second nature. This won’t be tolerable for some, but it’s the curse of having to adapt a mass of code for multiple devices.

A Satisfying Conclusion:

To say that Android is ‘as good’ as iOS is to describe it as a response alone, not a stand-alone product. Its chameleon-like shell allows it to be used in any number of configurations, and as a result is the darling of the tech industry. Its like a virus, and has been used as one, too: carriers, playing on the openness, will lock down various aspects of their devices and install bloated, useless applications to shill their wares.

But it’s also very powerful and forgiving: if you don’t like the keyboard your phone came with, there are dozens of alternatives in the Marketplace. Don’t like the contact application, or messaging? Replace it. Android is modular, and as a result it can also be lean. You just have to learn how to get rid of the stuff you don’t like.

If you’re going out to buy a phone for your wife or your octogenarian father, I’d be tempted to say skip Android and head straight for iPhone. But I’d like to give your wife, your father, the benefit of the doubt. Android isn’t the problem, it’s the perception of Android that is.

So, yes, I’d say Android is for you, insofar as is any mobile OS. It has the apps, the framework, the speed and the price. It also has the bugs and the inconsistencies to turn off the casual user. Most Android users will tell you they can never go back; you should let them show you first-hand.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.