“There’s the theoretical discussion, and then there’s the reality discussion. We’d rather underpromise and overdeliver.”

I’m talking to Bruce Rodin, Bell’s Vice President of Wireless Technology, inside a closet-sized room at the end of a long corridor, at the company’s Mississauga-based testing facilities. There are RF testing chambers to our right and, across the hall, a Tim Hortons teeming with caffeine junkies. He’s telling me about LTE-Advanced, which Bell recently launched without much fanfare in a number of Canadian cities.

Rodin is a technical guy, and talks with the kind of knowing confidence that leads you believe he’d use terms like “re-farming” and “southbound bandwidth” whether you could keep up or not.

It’s interesting hearing about all of this because Bell’s network, large swaths of which is deployed in partnership with Telus through a spectrum sharing agreement, is a bright spot in what has otherwise been a challenging year for the telecom giant.

There was its net neutrality violation case, where the company was held up as an example by Canada’s telecom regular of how not to act.

Another scuffle with the CRTC over basic television packages saw the company’s then-media head, Kevin Crull, interfere with CTV’s coverage of the decision, which led to his resignation a few weeks later.

Some legacy CDMA equipment – in old school brown, for good measure.

It’s also interesting following all of this amidst changes to the telecommunications landscape. In early 2014, Bell’s mobile subscriber numbers were surpassed by Telus, just as the two companies were attempting to build Canada’s widest-reaching LTE network to take on Rogers. But many Canadians don’t know about the agreement, and even the most informed insiders aren’t privy to the minutiae of its implementation.

What we do know is that, back in 2008, when Bell and Telus were offering CDMA service, both carriers realized that SIM-based standards like HSPA and LTE, the former of which Rogers was beginning to expand across the country, were the future. In order to get there quickly without overextending capital budgets, they would need to work together.

“When we committed to HSPA in 2008, we knew we were doing LTE; we just knew we were going through HSPA to get there.” It was largely the proliferation of the iPhone, which at the time Rogers offered exclusively, that spurred the move to faster 3G, but to Rodin the endgame was always ultra-fast LTE.

Cisco racks

But fourth-generation wireless networks, inside which LTE sits, are not just about speed; these deployments are more efficient, packing more bits into the same amount of spectrum as their HSPA+ counterparts. And as we often hear from the carriers, we’re in a spectrum crunch. You’d be surprised to learn, then, that Bell has done quite well for itself in the spectrum game, and now has enough to carry LTE signals on no fewer than four bands.

“Our focus is on Band 2, Band 4, and re-farm. Most part of the re-farm is just a software upgrade. It’s not like we’re replacing the radio or anything,” Rodin explains. For the untechnical, Rodin is divulging one of the many untold secrets of the wireless industry: that existing spectrum can be repurposed, or “re-farmed,” for use with newer standards.

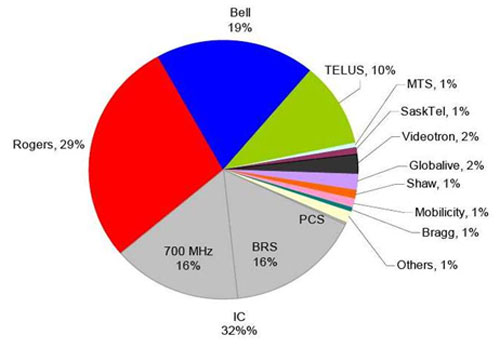

As recently as 2010, Bell was significantly behind Rogers in how much spectrum it controlled. Today, though Industry Canada has divested its ownership of both the 700Mhz and BRS (2500Mhz) frequencies, in addition to releasing an additional 50Mhz of AWS-3 spectrum, the breakdown you see above is little altered (caveat: carriers like Wind and Videotron have obtained a fair amount more in absolute terms).

In the 700Mhz auction, for example, Rogers snapped up what could be argued was higher-quality spectrum – Band A&B, what the company considers “beachfront property” – in all but the least populated regions across the country. Bell and Telus split much of the rest, cumulatively appropriating a larger number than their rival, but configuring these disparate bands to work together in some parts of Canada will pose a problem.

“In time, when we deal with the interference issues, we’ll work with Telus to open up those bands,” Rodin says.

My interview with Rodin was ostensibly to talk about LTE-Advanced, an umbrella term for a number of technical achievements that, among other things, allows two smaller channels, often side by side but many times not, to work together to achieve faster speeds with greater efficiency in more places.

To visualize this practice, think of a football stadium crowd surrounding a field. From far enough away, the audience is considered a cohesive hole, but for administrative purposes it is divided into quadrants. At some points in the game, the announcers will ask different parts of the crowd to chant together. One section could be asked to sing with another from across the field, another on its own.

LTE racks, divided by band

In the wireless world, under the LTE-Advanced standard, this is called “carrier aggregation,” and it’s being used in Canada to allow Bell to catch up with Rogers in an area it has traditionally trailed: capacity. Since Bell can now command different parts of the crowd to chant together, it has managed to bridge some of that performance gap.

So why doesn’t Bell shout this fact from the rooftops, like Rogers has with its now-defunct LTE Max branding and, more recently, its claim of being Canada’s first network to support LTE-Advanced?

“Maybe when we get a little more consistency with the rollout, it will be easier to articulate,” Rodin says. “We have 10Mhz in some area, 15 in another, 20 in others. In many parts of the country, we can’t get 20Mhz sounthbound until we shut down CDMA.”

That’s a problem with the piecemeal distribution of spectrum across the country: Industry Canada, in dividing the nation into sections and, in the interest of fairness, limiting larger carriers to how much spectrum they can bid on, has created a Frankenstein monster of wireless oversight.

Many Canadians balk at the idea that a company like Bell requires more spectrum to successfully run its wireless business. One of the most vertically integrated companies in the world, Bell owns just about every link in the chain, from the spectrum to the network to the stores, distribution and content. And that content is, increasingly, video.

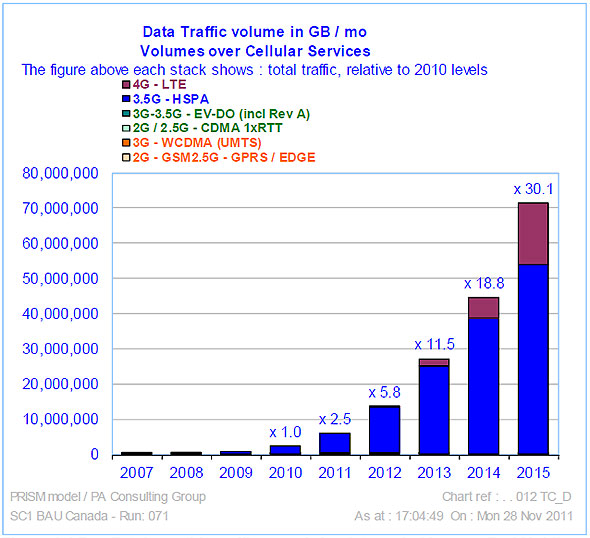

From a network operating perspective, video is expensive. It requires orders of magnitude more bandwidth than audio or static images and, increasingly, it is replacing those mediums as the default form of content consumed on mobile devices. In 2011, Industry Canada predicted that data traffic demand in 2015 would be 30 times its 2010 levels. But it wrongly predicted that HSPA would carry the majority of that traffic.

“This year we’ll get 50/50 split between LTE and HSPA,” says Rodin, who admits to being taken aback by how fast people took to the new standard. Thanks to companies like Qualcomm, Samsung and LG that pushed the technology while incumbents like Apple waited until it matured, Canada’s adoption of LTE, or Long Term Evolution, has been among the fastest in the developed world.

“We got here,” he says, looking at his phone, referring to his company and the country in which it operates, “being seven years behind the US in rolling out 700Mhz,” where the process began in 2008. Industry Canada, in deciding how to parcel out spectrum, typically takes its cues from the FCC, but despite similarities there are always considerations for legacy operations. Canada took longer to retire its analog television service, for which 700Mhz was originally plotted, but in doing so learned a lot from its American counterpart.

A million voicemails live inside this one cabinet

Canadian carriers actually benefited from this delay, as it allowed the advancement of baseband chips from Qualcomm to catch up to the reality of spectrum ownership. In 2011, when Verizon and AT&T began deploying LTE across 700Mhz, smartphones were not interoperable, despite “supporting 700Mhz” out of the box. In fact, AT&T and Verizon were accused of ordering equipment that actively blocked the signals of its competitors, so even if a device was later released that supported multiple bands across the 700Mhz spectrum they would neither roam, nor operate with a different SIM card.

“In the olden days there was an AT&T ecosystem and a Verizon ecosystem,” Rodin tells me, “but Apple changed that. They said, ‘We want to go with a global SKU; this is an Apple ecosystem.'” Apple released a single device, the iPhone 5s, that supported both Band 13 and Band 17.

Rodin stops for a moment, waiting for me to acknowledge that I understand. He waits a beat, then says, “all you need to know is that we’re going to cover 98% of Canada in super-fast LTE by the end of 2015.” He goes on to explain that while Rogers may have an easier time deploying 700Mhz because it owns that aforementioned “beachfront” property in the country’s most populated regions, Bell and Telus together own more spectrum and have just as many options to fill in the coverage gaps.

Bell treats its spectrum sharing agreement with Telus as one would the sharing of a chocolate bar with a diabetic: there’s tremendous enjoyment in one bite, but eating the whole thing would likely lead to disaster.

“We had plans about a carrier aggregation strategy that he had to delay in bringing to the standards body in fear of Telus and Rogers finding out. We took a hit on that,” referring to the combination of Band 2, 5 and Band 29, the latter a combination of unpaired channels in the upper 700 that can be used to offer additional downlink capacity in high-traffic areas.

“Network evolution is about managing data load,” he says, accounting for times, such as during popular sporting events, that video traffic is likely to be higher.

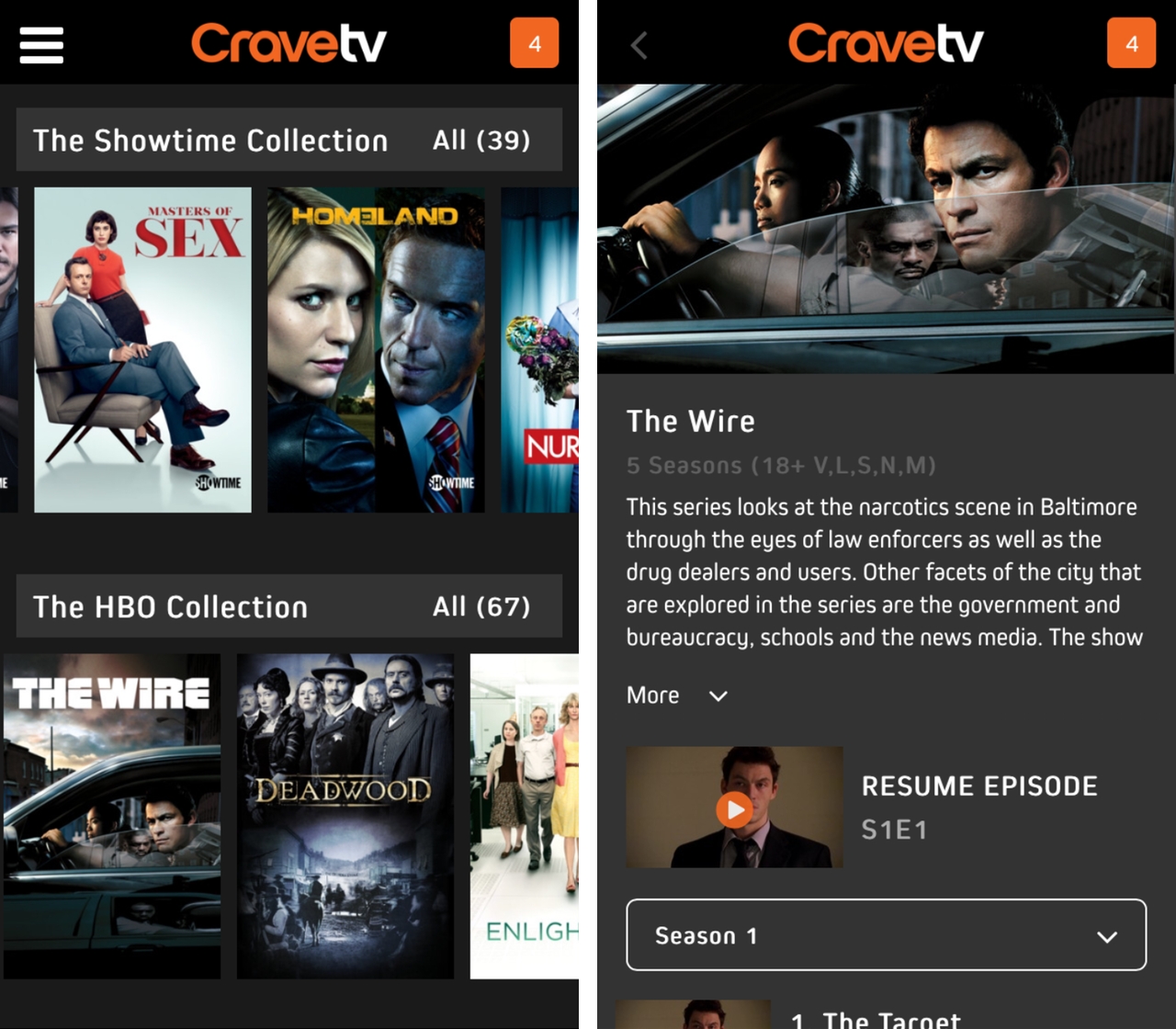

In December, Bell launched Crave TV, a hybrid over-the-air service that, though required to be paired with a TV subscription, exists as a standalone app on iOS and Android. According to Jon Taylor, vice president of Digital Products and Strategy at Bell Media, it took until now for the country’s networks to be ready for something like it.

“Crave exists in the white space between Netflix and ‘catch-up’,” he says, noting the increased amount on-demand and PVR’d content Canadians watch every day.

Bell considers itself the market leader of such projects, though Rogers and Shaw jointly launched their own hybrid-OTT product, Shomi, a couple of months before Crave. “Canadians still have more TV subscriptions than internet,” says Taylor. In 2013, the company retained the rights, through its purchase of Astral Media, to HBO’s current and back catalogue of content, including popular shows like The Wire and Game of Thrones. In January of this year, it did the same with Showtime, another distributor of premium television programming. Together, they comprise one of the deepest collections of high-quality TV content ever compiled, and Bell makes no apologies for wanting to retain control over who watches it.

On March 9th, HBO announced that it would begin offering a true over-the-top service that wouldn’t rely on a television subscription. Earlier in the year, at CES, Dish Network debuted Sling TV, a $20 per month streaming bundle that includes channels like ESPN, AMC, TNT, TBS and a dozen others. The trend appears to be gaining traction in the United States, but while Canadians will be able to access a $25 “Skinny Basic” television package by next March, it doesn’t appear that northern cord-cutters will be able to benefit from similar streaming services anytime soon.

“It’s not cheap to retain those HBO rights,” Taylor explains. He says that while creating an over-the-top service akin to HBO Now was considered – “You should have heard some of those early meetings” – the economics didn’t make sense. “When we announced Crave was going to be just $4 per month, people in the audience actually gasped.”

Taylor wouldn’t say how much of Crave’s intended binge watching is done over mobile networks, but Bell’s recent spat with the CRTC ensures that it won’t ever again be billing its customers differently for its own content than what it does for competitors like Netflix.

“Netflix is driving a path for innovation and content,” says Taylor. “We think [Crave] can work within the system.”

Where the device testing is done. This room blocks outside signals, ensuring that conditions can be rigorously controlled

Back in the small room at Bell’s quality testing labs, Rodin takes me through the series of chambers where his technicians perform tests on everything from legacy CDMA equipment – “We still need those for a while yet” – to the in-progress IMS, short for IP Multimedia Core Network Subsystem, infrastructure that will power Bell’s future, including the eventual rollout of Voice over LTE.

“The fastest way to get Qualcomm to stand up and take action is to tell them we’re talking to Intel.”

Every time Bell releases a new phone, its wireless performance is strenuously tested against all possible band combinations and tower deployments, especially since the company uses both Nokia and Huawei equipment. He also says that companies like Samsung tend to treat all carriers equally, and will work hard to support any and all frequency combinations. “We’ll play companies off one another,” says Rodin. “If Qualcomm doesn’t support something, or doesn’t want to, we’ll talk to Intel.

“The fastest way to get Qualcomm to stand up and take action is to tell them we’re talking to Intel.”

That’s how Bell continues to add customers. Last quarter, the company added nearly 120,000 wireless subscribers as it and Telus continued to steal postpaid clients away from Rogers. And while its key performance metrics like ARPU and data revenue continue to rise, keeping its shareholders happy, the company realizes that many of its customers are not.

Products like Crave TV are meant to counter some of those ideas that Bell is a monolithic, top-heavy institution with too many divisions, many of which don’t communicate with one another. Like Rogers and Telus, Bell is trying to improve its customer service practices, with better-trained representatives offering more comprehensive solutions and fewer hand-wringing conversations that end with, “I’m going to have to transfer you.”

“We have to be scrappy,” Taylor says, admitting that the team behind Crave TV treats it more like a startup than anything the company has heretofore done. “We’ve had to create silos of innovation,” he continues, a nebulous term that brings to mind the facile declarations by fake founders on HBO show Silicon Valley, the rights to which Bell owns. On content alone, Crave goes way beyond what Netflix Canada offers, but technologically the service needs to expand its offerings. While on iOS it supports AirPlay, Apple’s streaming standard, the app feels slow when compared to Shomi, itself an example of the other extreme: style over substance.

Rodin expects that Bell’s customers will continue to pack the airwaves full of video content, his company’s or another’s, and feels confident that his network is the best in the country. We end the conversation by talking about the future, of small cells and WiFi offloading, of Band 12 and Category 9. These are terms I devour as I seek to understand the intricacies of what it means to operate a mobile network in Canada.

Where Canadians see high prices and poor customer support, Rodin and Taylor, with the calm verisimilitude that appears unique to executives of vertically integrated companies, offer an alternative.

“We’re a dedicated group of people trying to put out a great product,” Rodin says. He repeatedly uses the word ‘commitment’ to illustrate that fact. But he has it easier than most of his peers: he doesn’t have to work hard to prove that Bell’s network, and Canada’s networks in general, are among the world’s most robust. It’s up to others, like incoming Bell Wireless president Blaik Kirby, to sell Canadians on its value.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.