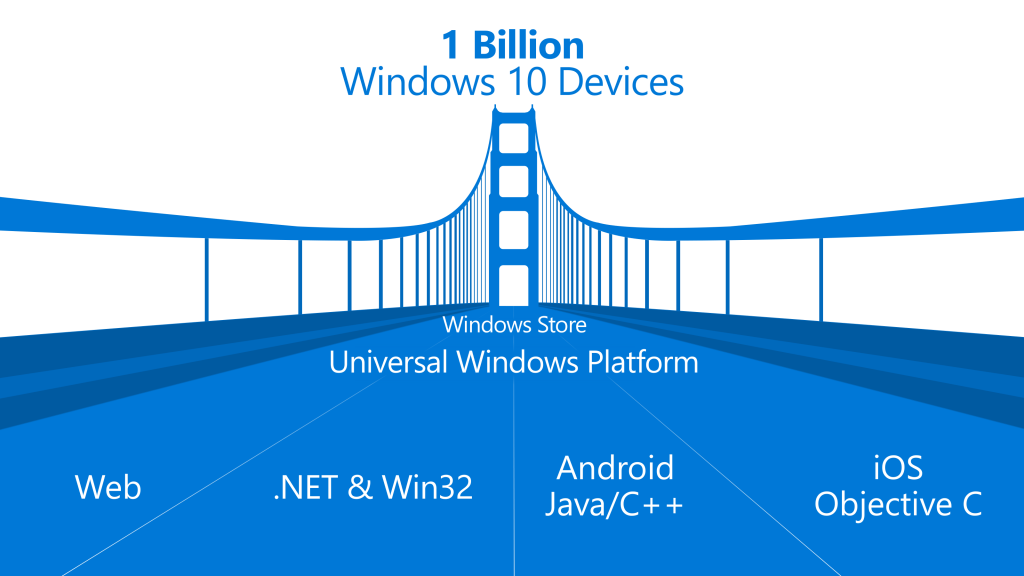

Nobody knew what to think. When Microsoft announced that Windows 10 devices would begin supporting Android and iOS apps with little modification to existing code, many developer attendees at the company’s Build conference applauded, but some took it to be a mea culpa.

The promise is certainly enticing: with minor changes, and hooks to non-Google services, Android apps will be able to run unmodified in an Android runtime on upcoming Windows 10-based smartphones. With a marketplace mired by omissions and abandoneware, Microsoft has, in one fell swoop, fashioned a positive outcome to its app problem.

The company also added iOS Objective-C support to its most recent Visual Studio 2015 build, highlighting that at least one major developer has already used it to port an iOS game to Windows 10 as a universal app without issues.

Microsoft did all this while continuing to push the essentialness of its Universal Apps platform, which began with Windows 8.1 but will roll out in earnest on Windows 10 this summer. There, the value proposition is quite real: developers can build apps that run properly on any Windows 10-based device, be it a small smartphone, a medium-sized tablet, an enormous 80-inch Surface Hub – or Windows Holographic, the company’s new augmented reality platform.

Microsoft believes that one billion devices will have access to Windows 10 upon its release, but that number is skewed by optimism. Hundreds of millions of those devices are still running Windows 7, and after the disaster that was Windows 8, most IT departments, despite tangible benefits over its two predecessors, are likely reticent to go near a new version of Windows.

There are numerous reasons why Microsoft should feel exasperated. Many developers have told me that even before Universal Apps, Windows development was in many ways a better experience than on iOS or Android. Hesitation to commit to Windows Phone came from a relatively sparse install base, and the single or dual platform strategies that accompany the leanness of most startups today. Windows Phone and Modern Windows have actually been quite good for the developers that invest; it’s just that so few do.

Microsoft only has to look at BlackBerry for an example of how this porting strategy may backfire. Starting with BlackBerry 10.3, the company began including Amazon’s Appstore, which hosts Android apps, on its devices. Amazon’s Kindle platform has struggled to attract high-profile developers, in part because the user base is much smaller than Google’s, but mainly because Amazon lacks core Google services that are increasingly essential to a user’s experience. Google Play Services are much more than just hooks into Google Now or Maps; they’re quickly becoming a way for developers to offload crucial elements, like notifications, onto Google’s shoulders.

It must be noted that Microsoft is taking a less open route than BlackBerry to bringing Android apps to its devices. You won’t be able to download an APK file to sideload an existing app; they will have to be compiled as Windows apps and, from what we understand, submitted to Microsoft in the same process as native apps are done today. Microsoft will therefore be able to perform at least some quality control, ensuring that only apps that have the appropriate hooks into its own services will get through.

The process is similar with Objective-C code, which Microsoft demoed on stage running in Visual Studio 2015 in the form of a basic counting game. Apple certainly wouldn’t let Microsoft distribute code meant for its own devices, so the process involves making changes to the projects that eventually lead to iOS apps and recompiling them for submission to the Windows Store.

Then there is Edge, the official name for Microsoft’s ‘Project Spartan’ browser. Modern web standards-compatible, Edge represents, according to head of mobile Joe Belfiore, “Being on the edge of consuming and creating.” The mantra of “everything to everyone” that made Windows 8 such a lacklustre product is still present on Windows 10, it just appears to be implemented more assiduously. Tablet UIs are truly touch-friendly, and desktop apps work properly with a mouse and keyboard. That philosophy extends to Edge which, though it retains a logo that will be ever-familiar to Internet Explorer users (and haters), leverages support for the Surface’s pen input (and, on other devices, one’s finger) to allow for annotation and sketching, using the web itself as a scratch pad for one’s thoughts.

It’s an ambitious, if facile, approach to remixing content, but considering how long the average laptop or tablet user spends in a browser, Microsoft’s plan could just work.

And if all else fails, there’s HoloLens and Windows Holographic. The company demoed the augmented reality headset on stage today, an impressive combination of the comfort and bleeding edge. Microsoft claims that all universal apps will live in “windows” on the HoloLens itself, and can be manipulated in real time by the wearer. There’s no question that Microsoft plans to leverage Windows Holographic as a way to bring excitement back to it developer community, but in the meantime it makes for a pretty impressive demo.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.