In the basement of a nondescript office building on the corner of Bloor and Yonge lies one of the hearts of Toronto’s free TConnect subway Wi-Fi network.

There’s no signage signalling the significance of this small room, but it’s here, and at two other so-called base station hotels, that countless cat videos, social media updates and emails pass through before making their way to transit commuters waiting to get on one of the city’s many subways trains.

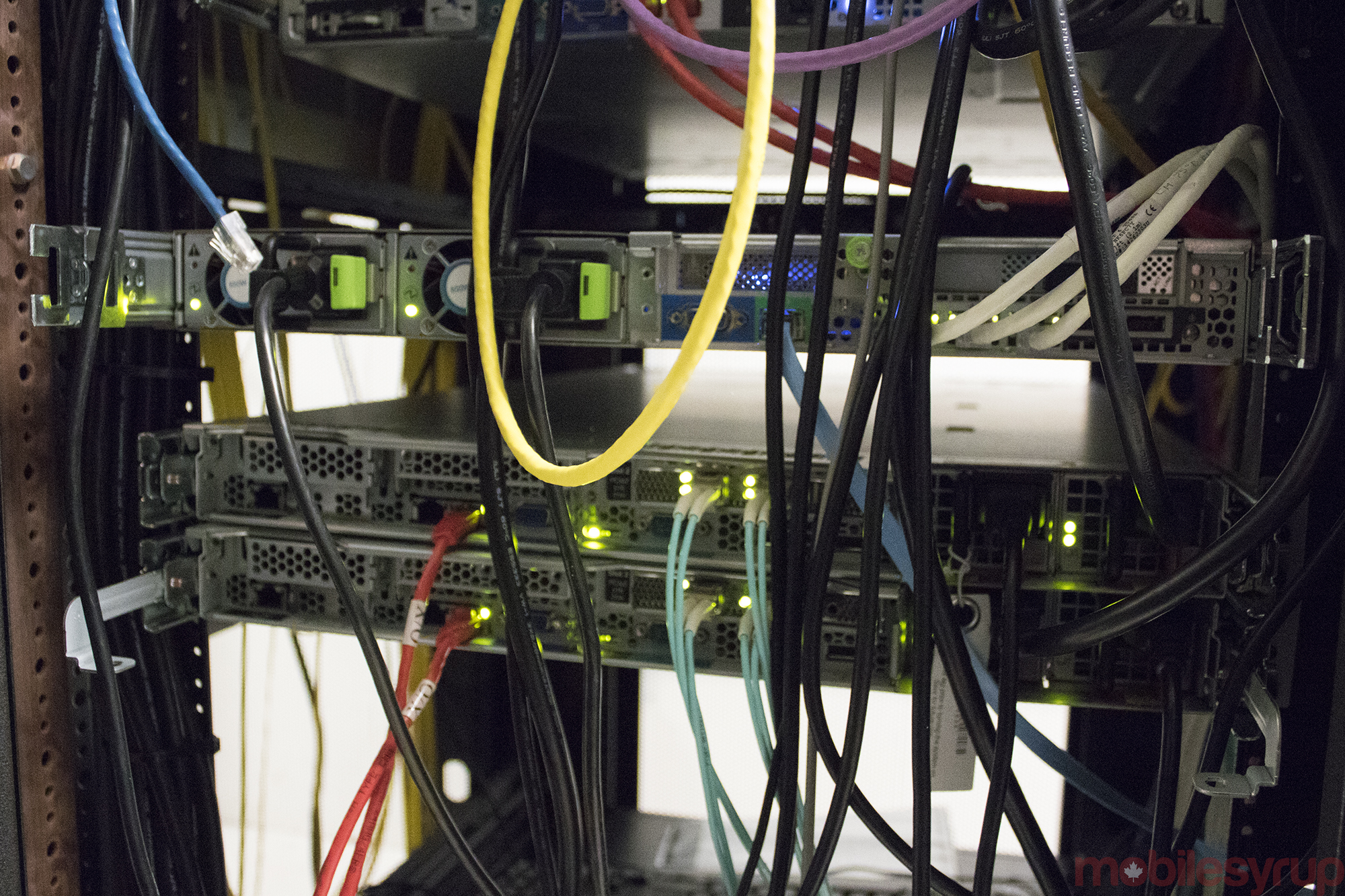

Even in winter clothes, it’s hard not to feel the chill in the air conditioned room. It’s also a noisy space, making it hard to hear what my interview subject, Ken Ranger, is trying to tell me.

Ranger is the CEO of BAI Canada, the company that in 2013 won the 20 year, $25 million contract to outfit the TTC with public Wi-Fi. Since TConnect launched in December of that year, his small team, and an army of contractors, have worked almost every day over the past two-and-a-half years to bring wireless access to the TTC. He’s taking time out of his day to show me the infrastructure behind the TConnect Wi-Fi network.

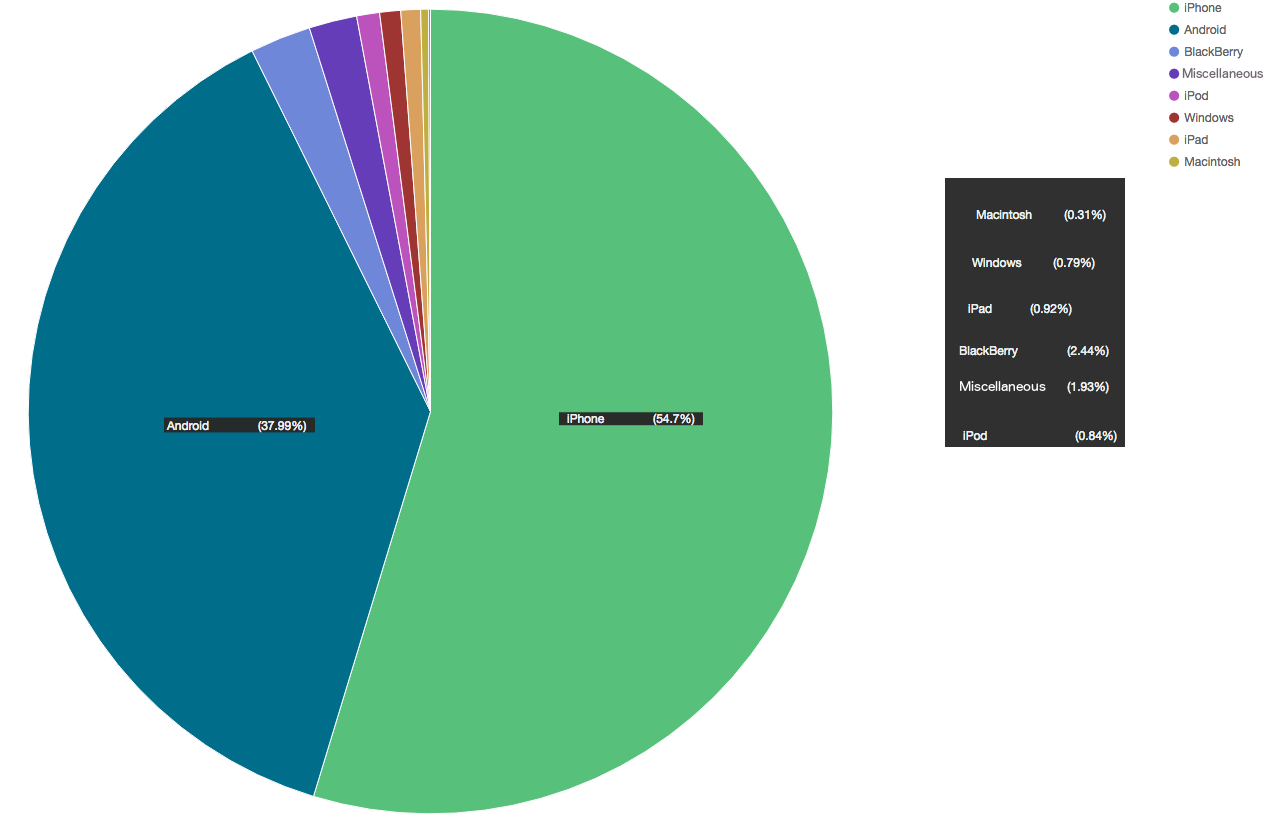

At the time of this piece, TConnect is up and running at 35 of the Toronto Transit Commission’s 69 currently built stations. In a given day, the network grants about 60,000 one hour sessions.

Since December 2015, when Wind Mobile announced a partnership with the company, BAI Canada has steadily added support for the carrier’s AWS network. To date, Wind Mobile subscribers can connect to their carrier’s network from 23 stations.

BAI expects to complete the rollout of its Wi-Fi network early next year. Sometime later in 2017, every station that has Wi-Fi coverage will also have cellular coverage. From there the company plans to add both Wi-Fi and cellular coverage to the more than 75 kilometres of subway tunnel that makes up the city’s subway system.

Like so many things associated with the TTC, it’s safe to say full underground Wi-Fi and cellular coverage is something Toronto’s transit riders feel is long overdue, a fact Ranger knows all too well.

“Every single time we announce we’ve built something, people generally say, ‘that’s great. We want more,’ he says after we leave the noisy confines of the company’s Bloor-Yonge hub. “It’s a wonderful position to be in.”

A number of factors have contributed to the seemingly slow rollout of public Wi-Fi on the TTC, and many of them have to do with the unique characteristics of the city’s subway system, both its operating circumstances and the aging infrastructure it’s built upon.

“The differences come down to the different characteristics of the subway. In Toronto, it comes down to the fact we have a heavily utilized system,” says Ranger. “The amount of traffic coming through these stations is twice as high as the New York system.”

According to the TTC’s own statistics, more than 745,000 people enter the city’s subway stations each weekday, making it a challenge for BAI Canada to build out and operate the TConnect network.

“The most challenging networks are the ones that are built for density, and we often hear that the most dense environments are places like stadiums,” says Josh MacKinnon, the designer of BAI Canada’s Wi-Fi network. He previously helped build VIA Rail’s first onboard Wi-Fi Network, as well as Amtrak’s onboard Wi-Fi network.

“I would argue that a subway system has even more challenges than a stadium environment. There are 40,000 people going into the stadium, we have 40,000 people going into a subway station every half hour. The churn of those people coupled with density makes it very unique to design for.”

“New York says they have a 24 hour subway, which is true. However, they also have multiple lines, so they can shut a line down and still use another line,” adds Ranger. “In Toronto, when the subway is closed for four hours, it’s shut down to revenue service, but it’s very busy with maintenance work going on every night.”

The addition of public Wi-Fi is just one of many of projects the TTC is undertaking to modernize its system. The commission is concurrently renovating multiple stations, making them both more aesthetically appealing and adding important things accessibility features like elevators; patching up decaying infrastructure; and rolling out new services like Presto integration.

“When we’re in the tunnels, that’s the only time we can work on network,” says Ranger. “For typical work nights, the guys try to get things ready and work in the less busy areas. But most of the work happens in that four hour window.”

Ranger is also quick to point out the fact that BAI Canada is not just building a Wi-Fi network. The plan was always to create a network that could flood TTC stations and tunnels with both Wi-Fi and cellular signals.

“It’s more than just Wi-Fi,” he says when showing me the equipment in the company Bloor and Yonge bay station hotel. “It’s a high speed network that has Wi-Fi on it. We call it a base station hotel because it holds space for all the carriers’ equipment. All we are is a way for them to get to their customers.”

Not knowing much about the actual backend hardware that powers these type of networks, I ask him if the city’s other major carriers — that is, Bell, Telus and Rogers — can simply hop on the network BAI Canada has built.

“The short answer is yes,” he responds. “We have other rooms that are available where they can simply stand up their equipment and hand us RF. This network was designed and built for every licensed carrier in the city of Toronto.”

As for when the big three might actually join the network, well, that’s more of a complicated question.

“What I can say is this network hosts Wind, and hosts Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, Sprint in the U.S. They are quite happy. The stations are built for them. We know that their customers would like it. I know that I would personally like it as a customer of one of the big three. These things take time. Their networks work great above ground and would work wonderfully below ground.”

After leaving the behind the underground room housing some of BAI Canada’s equipment, I’m led by Ranger and his team through a series of long corridors. Above me are pipes that safeguard the fibre optic cable that carries internet data to and from the subway. Eventually all the hallways and doors lead to Bloor-Yonge Station proper. It’s here where most Torontonians can see — and experience — the company’s work in action.

The fibre optic cable, hidden from public view with pipes, ends in a single room in Bloor-Yonge Station where there’s more of BAI Canada’s hardware. Each station where TConnect is online has one of these rooms. They have their own backup power supply and they’re air conditioned throughout the year.

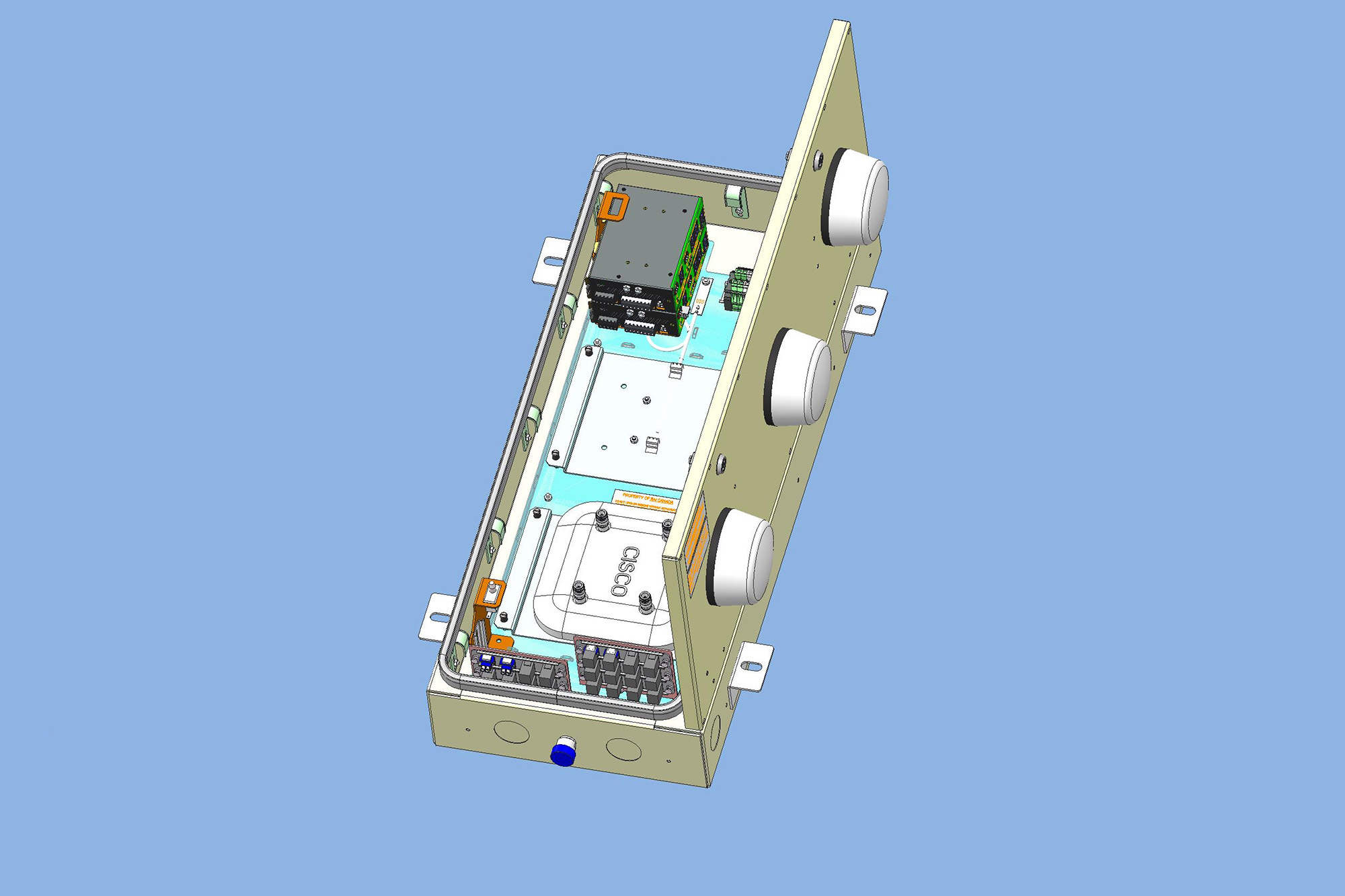

Interspersed throughout the rest of the station, approximately 30 metres from one another, are countless enclosures that house the equipment that beams wireless signals to any devices on the platform. While most of the equipment BAI uses to power its system is made up of off the shelf components, the enclosures themselves were designed by the company’s New York office. At present, there are some 400 of these units throughout the Toronto subway system, with more being installed every day.

These enclosures have since become an integral part of the TTC; they not only provide Wi-Fi and Wind Mobile coverage, they also power many other subsystems in the TTC.

For instance, in the stations where Presto turnstiles have already been installed, it’s those enclosures and the rest of BAI Canada’s network that handles the transmission of Presto card data.

“It’s a telecommunications network that you can layer on a variety of technologies on,” says Ranger.

Our conversation eventually leads to the fact there’s no Wi-Fi coverage yet in the city’s subway tunnels. “We have piloted some tunnel coverage on the Yonge line,” explains Ranger. The major issue, he tells me, is that the technological nature of Wi-Fi doesn’t make it the best fit for speeding trains.

“Cellular is a mobile technology, so the trains can go fast and the signals will be able to get to people on the trains, but WiFi is a different story,” he says. “WiFi is typically not a mobile technology. What I mean by that is to make your WiFi work on the train you will need to make the train a hotspot. Can we do that? Absolutely. But what we are going to focus on the short term is getting the stations out and getting cellular signal down the tunnel.”

It’s at this point that our tour is at its end. After thanking me for the fact I came to visit, Ranger sums up the whole enterprise.

“It’s just great to go and do things you enjoy and that people like to use,” he says.

“This is the only thing that I’ve ever done that my neighbours care about.”

Patrick O’Rourke contributed photography to this story.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.