Picture waking up in a 2D world to the voice of a little creature named Noot telling you it’s your first day at the Academy.

You rush outside your home, where you’re confronted by a few adorable monsters who challenge you to a math battle. Answering each question allows you to cast a spell on them and reduce their heart points.

Eventually, they run away but you’ve only just begun your journey. You are now a wizard-in-training in the world of Prodigy, a game most adults have probably never heard of, but that nevertheless has over 24 million players.

The players are primarily North American elementary middle school students — in fact that number represents roughly half of all five to 13-year-olds in Canada and the U.S. — and they’re using the game both for fun and to learn essential math skills.

Of course, Prodigy isn’t the first educational game to hit the market, but it is unique in its strategy. The game, which is a well-developed Pokémon-style online RPG, is offered for free to educators and students and is based on HTML 5, making it possible to run the game even on out-of-date school computers. This accounts for the high number of schools — 30,000 — and thus students, who use it to learn curriculum.

Prodigy makes money by making the game so irresistible that kids ask their parents for a paid membership ($8.95 per month or $60 per year) to unlock bonuses. For the parents’ part, they get a more detailed breakdown of their child’s progress. No additional educational content is unlocked — just extras, like cool hats or pets.

The company has also recently delved into physical toys, which unlock digital pets in the game.

Above: Prodigy co-founders and co-CEOs Alexander Peters (left) and Rohan Mahimker (right).

“It’s all engagement, unlike a lot of other math products,” says Rohan Mahimker, co-founder and co-CEO of Prodigy in a recent interview.

“If kids aren’t enjoying the game and if they aren’t asking for the upgrades, we essentially don’t make any money as a company. I find the motivation on our side, to keep kids engaged, is kind of aligned [with educational goals].”

The game is available to play both offline and online. Online, players can join a selection of worlds and battle each other in addition to the monsters that populate the world. Users can add each other as friends and visit each others’ houses, but can’t chat to each other, keeping socialization minimal.

It’s all about leveling up your character and collecting pets through Pokemon-style combat that requires you to solve a math question to use every attack. As you travel through the world, you also complete quests that work towards the ultimate goal of collecting the “strange and mystical wardens” that once guarded Lamplight Academy.

For an educational game, it’s got a pretty avid following. Millennials might have fond memories of Reader Rabbit and Carmen San Diego (I know I do) — but there was no real community around those games at the time. Prodigy has a 506-page wiki actively maintained by players who are level 250 or higher. There are YouTube gameplay videos with over a quarter of a million views.

And kids are talking about it; I was forcefully introduced to the game by my little cousins at Rosh Hashanah dinner. They told me some kids took it too seriously, indicating they were cooler than that — but still played several battles “just to show me the game.”

Above: A screen urging players to sign up for paid membership.

The company started as a fourth-year project for Mahimker and his co-founder Alexander Peters at the University of Waterloo. Both were undergraduate engineering students in the mechatronic engineering program and both had a passion for math and education.

Looking back at how he learned math as a kid, Mahimker says it was mainly through an after-school tutoring program and worksheets, while in his spare time he was obsessed with Pokémon.

“According to my Mom, I wasted two years of my early life playing Pokémon,” Mahimker recalled.

“So we said, why can’t we blend these two experiences? Why can’t learning math be as engaging, if not as addictive, as a Pokémon-style video game?”

Mahimker noted they also wanted to address the issue of math anxiety, wherein kids feel hyper anxious about the prospect of doing math, as well as overworked teachers who can’t stretch themselves thin enough to adequately attend to each one of their student’s math-learning needs.

“Math is very cumulative, so let’s say you’re a grade one student and you’re getting a 90 percent in math, which means you know 90 percent of the content, but you don’t know 10 percent of the content. Then you go on to grade two, and let’s say you get an 80 percent, you don’t know 20 percent of the content. It keeps accumulating, so eventually by the time you get to middle school or high school, there’s a lot of that content that is missed,” says Mahimker.

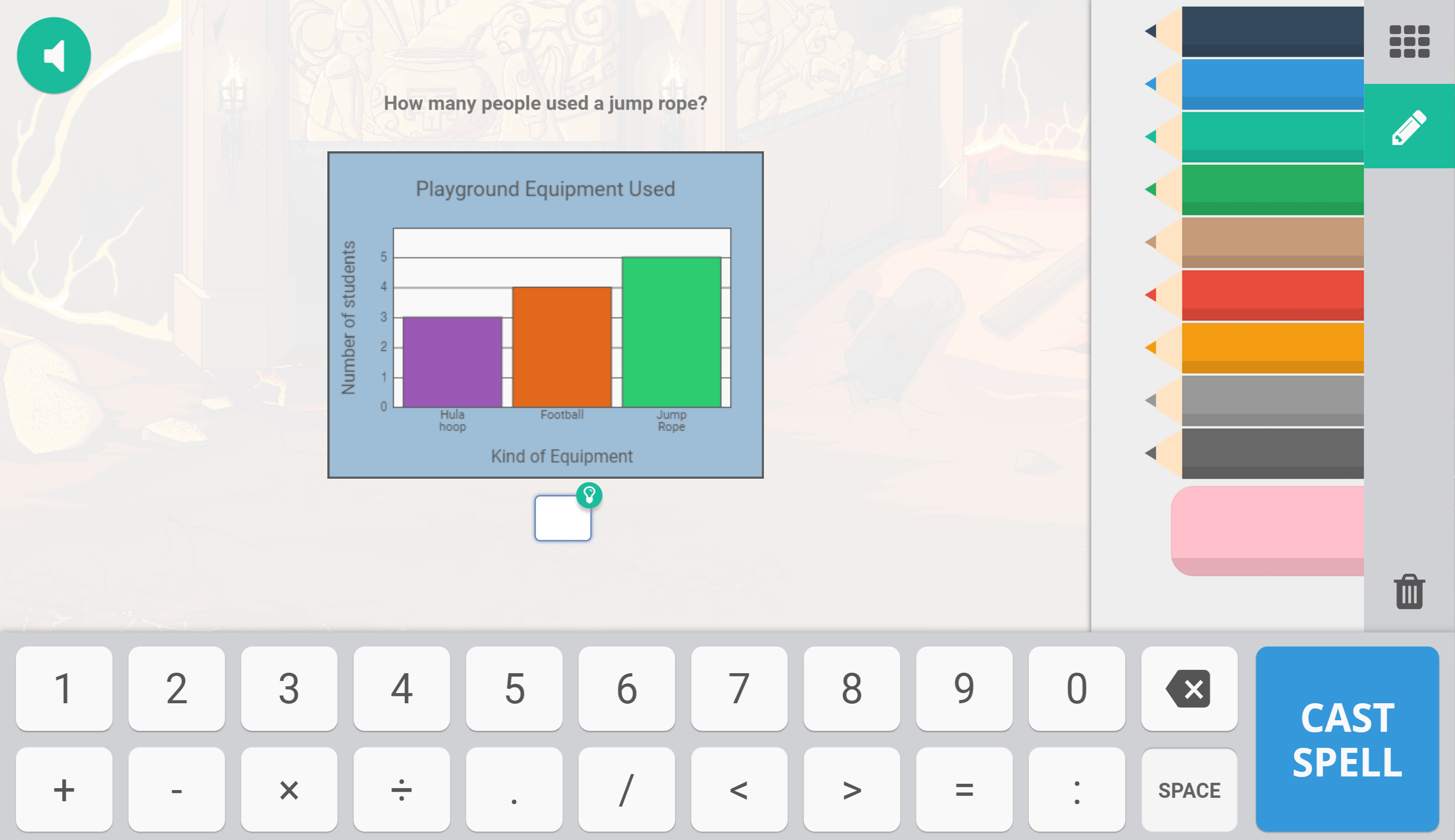

Above: A Prodigy math question.

He notes that a practice tool like Prodigy aims to solve that issue by helping identify knowledge gaps to teachers and parents and helping to close them so there’s less cumulative uncertainty building up and they’re more likely to continue to pursue science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) in the future.

After testing with a few private schools, the game officially launched in Ontario in January of 2013 with about 3,000 students focused mostly in Hamilton.

Spreading across Ontario, the game got to about 130,000 students by the end of that year, and by the following year they’d made it to about 1.2 million players and expanded to the U.S.

Now standing at nearly 25 million students, the game is continuing to grow at a rate that demands aggressive hiring.

The company is currently at just under 120 employees and wants to hire 100 more in the next year, but Mahimker says they’re unable to find the tech talent they need at their breakneck growth pace.

“It is challenging because there is a real shortage of tech talent here, in Ontario,” says Mahimker.

“I think this is a symptom of the very issue we’re trying to solve.”

Above: Prodigy employees working.

Unfortunately, kids learning on the Prodigy system today won’t exactly be able to help the company’s short-term growth problems.

That’s why the Burlington, Ontario-based company is leaving behind its former stealth mode approach and doing all it can to recruit.

From entering awards to writing op-eds, Prodigy is broadcasting the opportunity loudly.

“It’s all across the board, it’s not just development, we’re looking for developers, game developers, QAs, marketing, recruiting. It’s really all the functions you need in any startup,” says Mahimker.

The issue isn’t a new one — tech companies not only in Canada but across the world have long spoken out about the problem. The Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC) reported in early 2016 that there won’t be enough qualified workers to fill more than 218,000 new information and communications technology jobs in the country by 2020.

On top of that, vying for talent against larger companies like Shopify and Google, which recently announced a new Eastern Waterfront headquarters is coming to Toronto, is not easy.

So, like any good startup would, Prodigy is offering all the perks you’d expect.

Above: Employees draw on the window at a Prodigy office party.

“We’re probably one of the more exciting companies in Burlington,” says Mahimker.

The company’s office features ping pong tables and video game nooks, along with free snacks and drinks. Employees get to set their own office hours, gain stock options and – perhaps most excitingly — have access to a $1,200-per-year discretionary learning and gym fund.

“We’re an educational company so what we try to do is invest a lot in making sure that people are constantly upgrading their skills,” says Mahimker.

Employees can also propose larger ticket learning experiences, if they’re so inclined. Additionally, Mahimker says the company is willing to put time into training green engineers through a dedicated internal accelerator program.

Mahimker says the educational mission of the company helps to draw some employees in, as well, but that’s not always much help when competing against Shopify or Google for a senior full-stack developer.

As the team grows, Prodigy is also eyeing the prospect of a Toronto satellite office — but not one in the U.S. just yet.

Above: Employees talk and drink champagne at a Prodigy office party.

“We have considered it,” says Mahimker, “But it’s actually a lot better to be based in Canada. There is a lot of talent here, the war for talent is more intense in Silicon Valley.”

Mahimker also says the people working in Silicon Valley tend to be more transient, moving from job to job after only a year or so at a given company.

“It’s a stable environment and culture,” he say, adding: “There is some government support available so when we were initially starting out, we got a few government grants that helped get us off the ground, and that in combination with friends and family funding has allowed us to essentially bootstrap and we haven’t had to look externally for any VC money.”

He also notes that the cost of living and the cost of labour is a lot lower than in places like Silicon Valley.

Still, for all its upsides, Prodigy no doubt wishes there were more grown-up math wizards on the market — and unlike most Canadian startups that gripe about the hiring situation, at least Prodigy is working on a fix.

If the company sustains its growth, the day will come not too far in the future when one of its former wizard trainees does enter its doors; a fitting conclusion to Prodigy’s ongoing quest to bring more kids into the STEM fold.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.