Since launching in September 2017, Canadian-made Cuphead has taken the gaming world by storm.

The run-and-gun title has sold over two million units to date, while the game’s developer, Studio MDHR (founded by brothers Chad and Jared Moldenhauer from Saskatchewan) has since gone on to win several awards from prestigious ceremonies like The Game Awards in December, and the Annie and D.I.C.E. awards last month.

Speaking at a Q&A panel at the Enthusiast Gaming Live Expo in Mississauga, Ontario this weekend, Chad and his wife Maja went over how a team of people who had never made a game before, ended up releasing such a massive debut hit. On Cuphead, Chad served as art director — with Jared assuming the role of game director — while Maja handled many of the actual art duties, as well as executive producing the game.

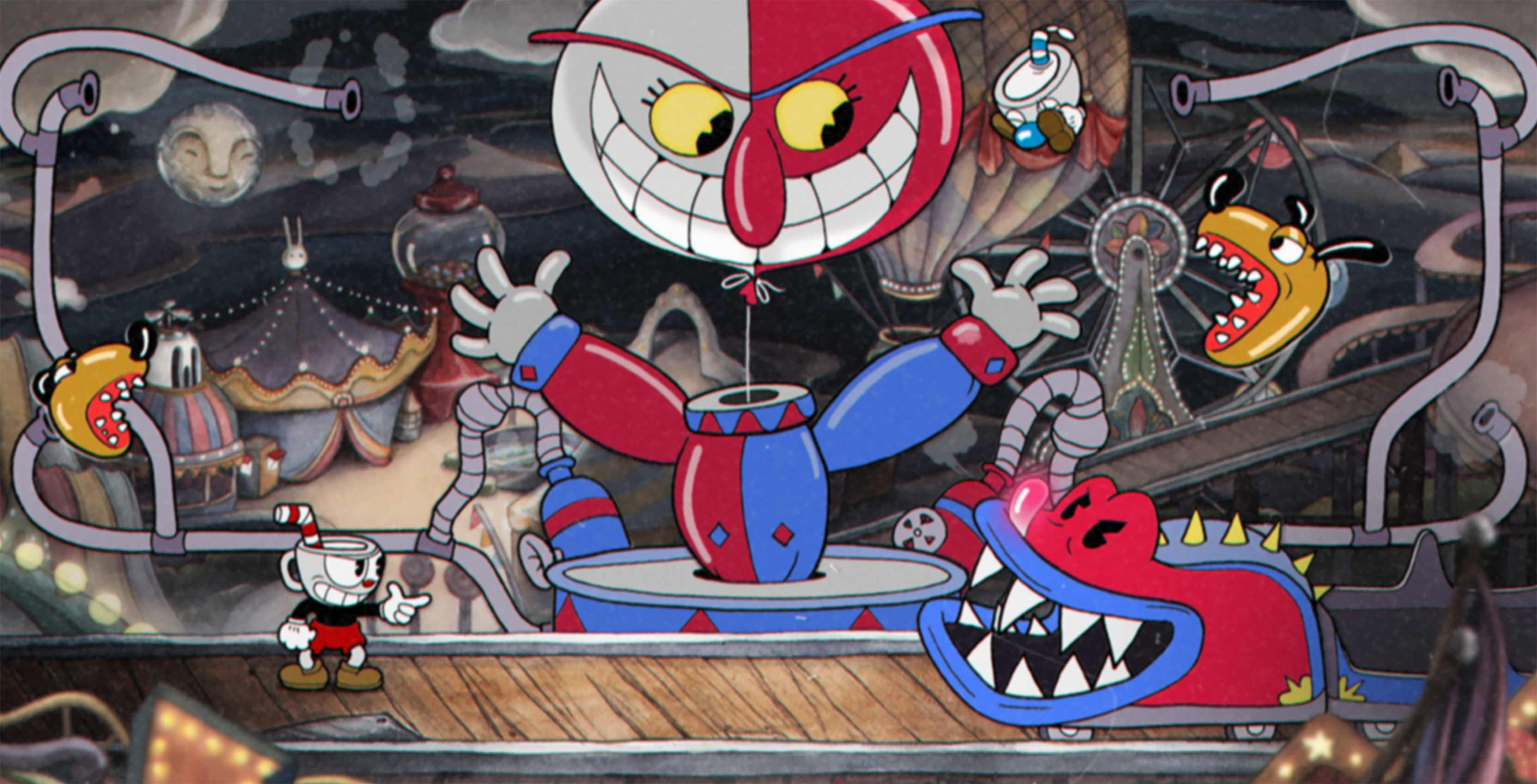

Understandably, a small first-time Canadian studio making a new intellectual property that also served as one of Microsoft’s flagship Xbox One and PC exclusives can feel a great deal of pressure. However, the Moldenhauers say that by unflinchingly staying true to their vision — beautiful hand-drawn 1930s-style animation meets Contra-esque run-and-gun gameplay — they were largely able to avoid feeling overwhelmed by any expectations from the gaming community.

“One of my favourite things [after announcing Cuphead] was seeing a lot of comments from people thinking this was just a cutscene, that there was no way a game could actually look like this,” Chad said.

“And since we knew it was already running and we were playing it, that was a funny inside joke to us. It helped cement the idea that we could make a game we love without a bunch of research or worrying about what the market could handle and still reach an audience.”

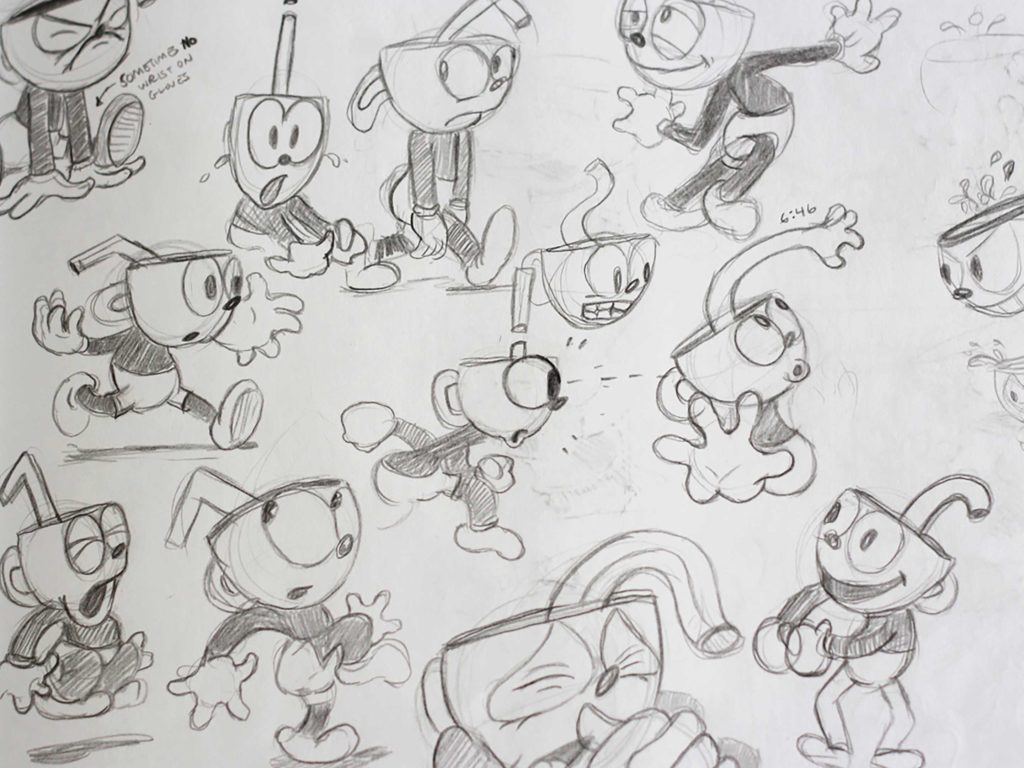

The initial skepticism stemmed in no small part from the fact that Cuphead‘s aesthetic was created by painstakingly hand drawing every frame of animation on paper, which would then be inked and inserted into the game. That level of physical work going into a game’s presentation is largely unheard of in the medium, prompting many people to feel the team was too ambitious.

However, Maja said the team’s confidence to pursue their game development dreams helped them ignore anyone who told them they wouldn’t succeed. “The number of times we heard ‘it’s too hard, guys, you gotta scale it back if you’re going to market this to a bigger group,'” she said. “But after the second or third word it would just start blurring in our minds because we just knew exactly what we wanted and we were going to make that, and nothing anybody said was going to be able to distract us.”

Studio MDHR’s humble beginnings also helped ensure project goals were always kept in check. “We never went into this with the expectation of selling so many units and hitting these markets and having this merch and stuff like that,” Maja said. “It was never about that, so I think that alleviated a lot of pressure as well. It was just about making a game we loved for gaming’s sake.”

At the same time, she said Microsoft not only helped back Studio MDHR financially, but also provided the team with “invaluable” support on various elements related to creating the game, including attending trade shows and marketing the game. This was especially essential for the team, given that the Moldenhauers quit their jobs and remortgaged their homes to go all in on game development.

Interestingly, Studio MDHR managed all of this in spite of the fact that the Ontario-based Moldenhauer team members hadn’t even actually met approximately 40 percent of the team in-person, according to Chad. This is because many of them were working remotely from different areas, like British Columbia or California, collaborating primarily through project management and team communication software called Basecamp.

The reason for hiring team members who were farther away, Maja said, is because it proved challenging to find game artists who were proficient in the ‘dying art form’ of 2D animation.

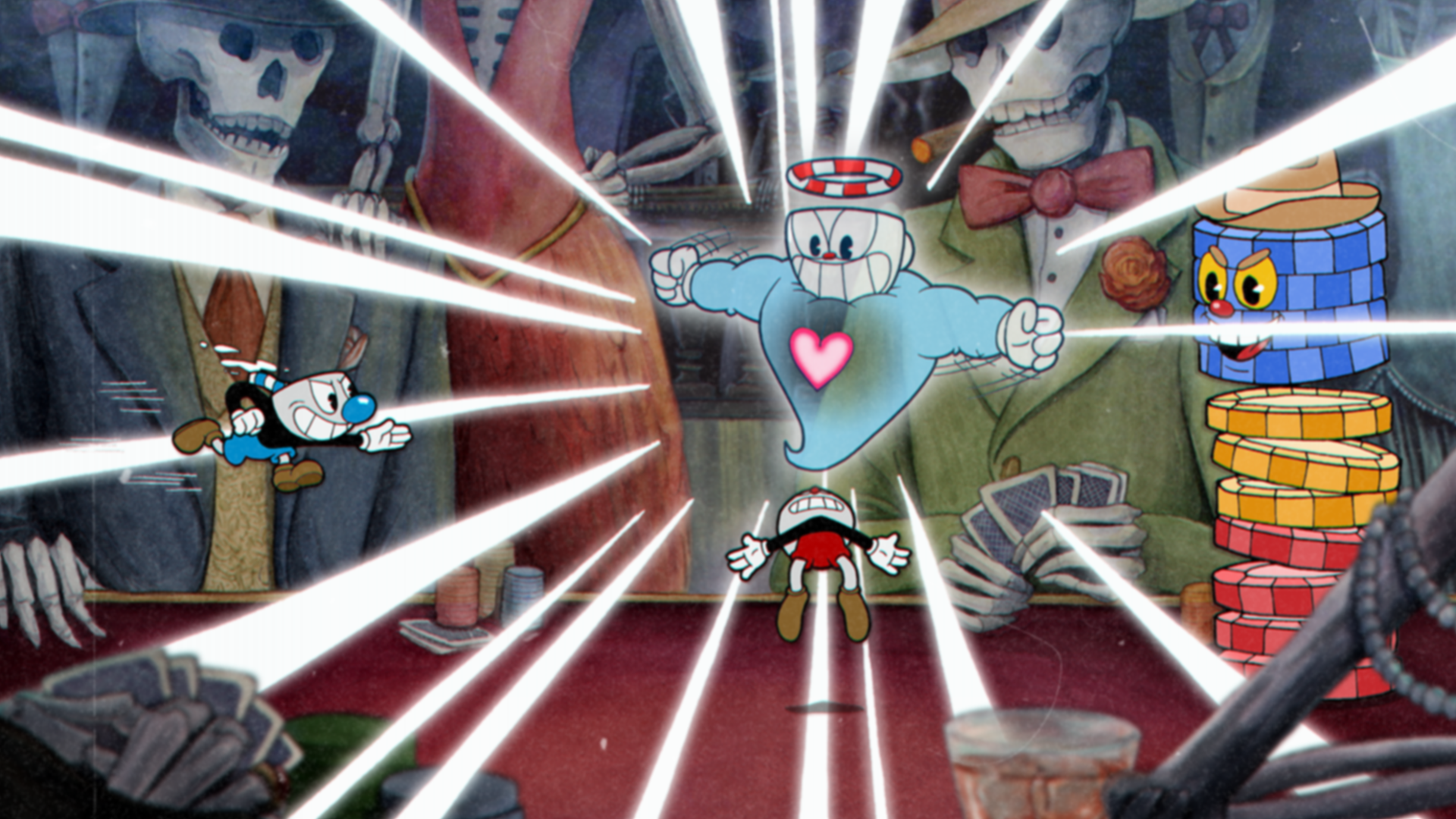

It was particularly important to get the right artists for the job, Maja said, in order to meet the high art standards Chad set upon the team. “Do you know that there are 6,000 individually drawn raindrops on [Cuphead dragon boss] Grim Matchstick’s final phase that [Chad] wouldn’t let us reuse?” Maja said with a laugh. “He was like ‘no, no, no, in The Little Mermaid, every bubble is unique.'”

“The art director on The Little Mermaid, I can’t remember who came to him, but he said ‘there’s technology now, we can replicate the bubbles and reuse stuff,’ and [the art director] was steadfast on ‘never, everything has to be hand-drawn,'” Chad explained.

“So I kept that rule on 95 percent of the game, when bosses have dust effects when their feet hit the ground or sparks and stuff come off of them — it’s all original and catered towards that boss. So we kind of went crazy.”

Chad said that during Cuphead production, he had watched up to two hours of old animated movies for reference and inspiration every day over at least six or seven months “One of the main things as we developed the game is I didn’t want to to have anything in the game that seemed like it didn’t fit in the era,” Chad said. “So if an animator was working on a boss that threw a hammer, they would say ‘hey, this hammer looks really cool!’

“But then I would go and research and look to see how hammers were drawn in cartoons, how they were drawn in annual reports or posters in the era, just to make sure we weren’t bringing anything modern or too old into the game. There’s a ton of research to make sure everything looks the way it should.”

For the Cuphead character alone, Chad estimates Studio MDHR went through 300 to 400 different concepts before deciding on the final design.

Outside of its art style, Cuphead is perhaps best known for being an incredibly challenging game. The reason for this, Chad said, goes back to the idea that they wanted to make a game that they loved and hoped others would as well. “The difficulty comes from [the fact that] we grew up in the mid-80s and early 90s and there was really no such thing as a ‘hard game’ — they were all hard,” Chad explained.

“You’d pay $70 for a game that was maybe 40 minutes long so the developers made sure they were super hard. But we didn’t see it that way growing up, it was just, ‘that’s how the game played.’ It’s only because of our history that Cuphead is this hard. It’s not intentionally hard, it’s just the style of game that we wanted to make.”

Chad also addressed the controversy surrounding Cuphead‘s ‘Simple Mode,’ which features easier boss encounters but locks off the final 10 percent of the game. For Chad, the high degree of challenge drives the entire experience — something, therefore, that the team didn’t want to make any compromises on.

“We like the idea that in gaming, at least in this style of retro gaming, it feels like you’ve completed something if you have to give it your full effort,” said Chad. “So the choice to ‘gate’ the people who only played on easy in our minds was a pretty easy one to make. Because when the people did earn it, it would feel much better than if anybody could just play it on simple mode and beat the whole game and say ‘okay, I beat it.'”

On the subject of completion, now that Studio MDHR has had a handful months after release to focus on promotion instead of development, the Moldenhauers say the team is “eager” to get working on a new project. While they’re still figuring out what, exactly, their next game will shape up to be, Chad said he knows it’s going to be even more complex in its design and scope.

“Now, when we get to making the next project, we’re going to try to one-up ourselves,” he said while laughing. “I don’t know if we’ve learned any great lessons [from Cuphead] because we’re going down the same hell path again.”

Image credit: Studio MDHR

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.