Montreal-based startup, Boréas Technologies, is on a mission to bring the haptic feedback so common in mobile device touchscreens over to the infotainment displays in vehicles.

Boréas develops haptic tech for both consumer and commercial applications and introduced the BOS1211 at CES 2020. It’s a low-power circuit that can enable what the company calls “high-definition (HD) haptic feedback” in the human-machine interfaces (HMIs) so commonly found in vehicles today. That certainly means infotainment screens, but also steering wheels.

The haptic tech called CapDrive was on display to showcase a partnership with TDK, who is currently the world’s leading supplier of piezoelectric actuators — the modules that power haptics in vehicles.

Making the case

Touchscreens are now standard fare for most vehicle makes and models, except they don’t offer any haptic response when tapping on them. IHS Markit forecasted that there would be 52.8 million automotive touch displays in 2020, and growing at an annual clip of 4.6 percent. Boréas cites a research study from Stanford University that concluded drivers responded better to haptic feedback on the steering wheel over audio feedback from a voice assistant.

The jury’s still out on whether tactile feedback carries a distinct advantage over voice control or vice versa, but Boréas and TDK are convinced the cognitive load on the human brain is lower when haptics are in play.

“The quickest way to input a command in a car is a touchscreen,” says Simon Chaput, founder and CEO of Boréas, in an interview. “The issue is that drivers tend to look at the screen for too long because there’s no feedback when pressing it, and so eyes stay focused there until the screen changes or until the command is secured by the system.”

And so, the thinking is that haptics in the screens can offset that by giving drivers a tactile way of knowing they did something. Haptics are often driven by actuators residing underneath the display. Not all the technology behind them is the same, but Chaput says his startup’s implementation works well with TDK’s own piezo actuators.

What is now Boréas’ current technology was first developed at Harvard, starting in 2013 when the company was founded. Chaput and his team have mostly worked on research and development, but are now ready to bring this to automakers (through TDK) who may be interested in deploying it.

Feeling the touch

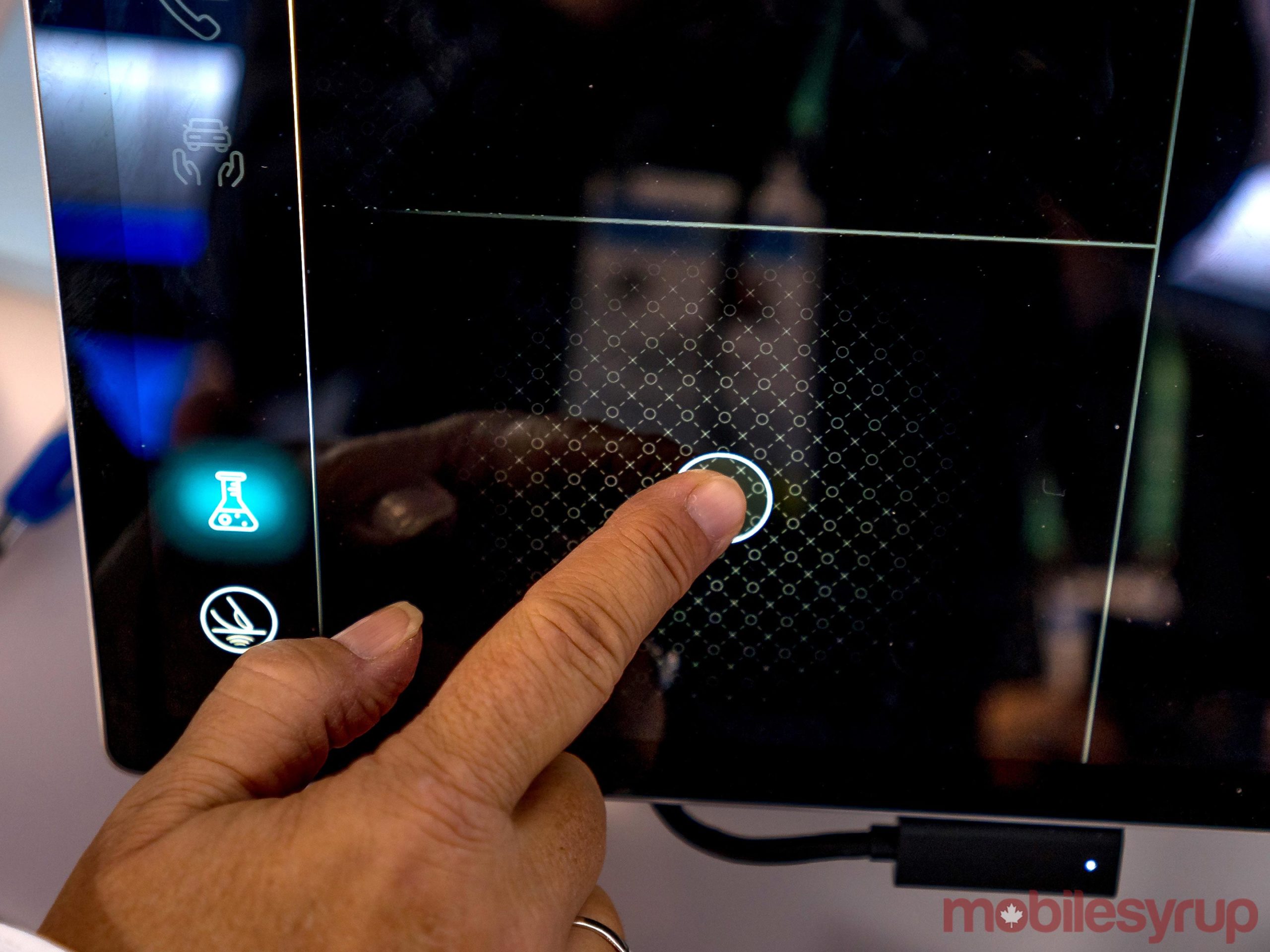

There was a live demo of how the haptics would work on a mockup infotainment screen that was developed by a different company called Immersion. While the interface onscreen wasn’t anything that is available on the market, and the BOS1211 itself wasn’t embedded inside, the idea was to show how the haptic feedback would apply to a standard interface.

What was initially obvious was the familiar tactile feel of something vibrating underneath the display. It wasn’t altogether different from what it would be like on a phone or tablet. The sensation is also scalable, so a prospective automaker could choose to offer different sensitivity levels.

I asked whether it would be possible to make part of an interface more responsive than another. For instance, if there was a menu bar at the bottom, could that portion vibrate more than another portion above to give the driver a more distinctive feeling for the screen without looking at it. Part of the demo showed how moving away from a specific point could increase the vibration, letting drivers know they actually aren’t hitting the right spot.

“It’s very similar to a traditional interior where you would feel approximately where the physical button is, you’ll be able to guide your fingers to it, and then you’re able to press it,” he says. “So, the idea is the same with a touchscreen, you need to have the haptics to guide fingers to where the command is, and tell the user that the screen registered it.”

While this might all seem elementary based on the ubiquity of haptics in mobile devices, they’ve been deployed in other areas in the car to date. Steering wheels are one, as are touchpads in specific models, but screens have been left out of the equation.

Chaput says the cost to implement it is lower with Boréas’ and TDK’s technologies. I saw a demo on a tablet that emulated what a Samsung Galaxy Note device might be like. The haptics made writing feel more like pen on paper than current iterations. TDK reps said there are “talks” with certain manufacturers, but did not reveal who they were.

The same goes for automakers. There’s interest, they say, though it’s not known who they might be. And with the typical vehicle development cycle of a few years, it’s hard to guess when we’ll see cars using this kind of tech.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.