After years of rumours, Apple’s first ARM-based M1-powered Mac devices have finally arrived.

While early reports indicated that Apple would start the two-year transition to its own proprietary silicon by releasing a refreshed version of the now-dead 12-inch MacBook, the tech giant has instead jumped in head-first with a wide range of new M1 Macs.

Likely because they’re the tech giant’s most popular devices, Apple has released three M1-powered Macs: the MacBook Air, the 13-inch MacBook Pro and the Mac mini.

Apple, as expected, makes lofty claims about its first ARM-based system-on-a-chip (SoC). The chip itself is one of the first in the industry to be designed with 5-nanometer technology. Further, instead of individual chips for the CPU, GPU, security, I/O and memory, the M1 combines everything onto a single discrete SoC.

While this has several benefits, it primarily allows a Mac’s various components to communicate more effectively.

Though I’ve only spent a brief amount of time with all three new Macs, including the MacBook Air, the 13-inch MacBook Pro and the Mac mini, most of Apple’s claims regarding its new chip seem accurate (more on this later).

Apple says that its 8-core CPU features four high-performance cores and four high-efficiency cores, offering an up to 3.5x increase in CPU performance. On the GPU side of the equation, the 7- or 8-core GPU (the entry-level MacBook Air features a 7-core GPU due to chip binning) amounts to up to 6x faster graphics performance across the board.

There’s also a 16-core Neural Engine capable of computing 11 trillion operations per second, and 16GB of RAM built directly into the M1 chip.

Make no mistake, what Apple has accomplished with the M1 chip feels, at least in some sense, like a generational leap forward for the Mac line in terms of raw power.

That said, the transition away from Intel’s chips isn’t entirely smooth.

Note: This story is a brief look at Apple’s M1 chip and new Mac devices. I’ll have full reviews of some of Apple’s M1-powered Mac computers in the coming months.

Rosetta II emulation and growing pains

For apps to truly take advantage of Apple’s new chip, they need to be entirely redesigned to run off the M1.

While the tech giant’s entire software suite, including Final Cut Pro, Logic Pro, Xcode, Create ML, FaceTime and more, have been optimized for the M1 chip, the majority of major third-party app developers still need to update their software. That said, there are some M1 versions of third-party apps already available, including DaVinci Resolve and Pixelmator Pro 2.0.

For many, however, the M1 version doesn’t exist or is still in the works. This includes Adobe’s entire Creative Cloud software suite, which I use daily to do my job. Lightroom support is coming soon, and Photoshop will arrive at some point in 2021. When the rest of the Adobe CC suite will transition to Apple’s M1 chip remains unclear.

The same can be said about nearly all the software I use on my MacBook Pro, including Microsoft’s Edge browser, GIF Brewery, Private Internet Access, Logitech Options and more. Google Chrome also doesn’t have an M1 version. As for Edge, it’s worth noting that Microsoft maintains a version of the browser compatible with ARM-based CPUs for Windows devices like the Surface Pro X, so it’s possible an M1 variant for Mac computers isn’t far off.

This Intel-based software is emulated through Apple’s new Rosetta 2 platform, an evolution of the Rosetta software the company used during the transition from PowerPC to Intel processors back in 2006.

While Rosetta 2 makes an admirable effort to emulate Intel Mac software, the experience isn’t perfect. Launching each app for the first time typically results in it taking twice as long to load, especially when it comes to Adobe’s CC apps like Photoshop and Lightroom. Once the apps are open, performance is roughly on par with my experience using the apps with the Intel i5 13-inch MacBook Pro (2020) I typically use. However, I did encounter the occasional bout of lag when working with multiple RAW image files.

I’ve also experienced several issues with Logitech Options, the Mac software I use to connect the company’s M720 mouse and K850 keyboard via a USB unifying receiver. Likely because Logitech’s connection software is being emulated, both the keyboard and mouse experience lag when connected to Apple’s USB-C-to-USB-A adaptor and the third-party USB-C-to-A hub I’ve been using for several months. Bypassing the unifying receiver and connecting directly through Bluetooth seems to solve the problem, but I still encounter the occasional mouse pointer stutter.

Then there’s Microsoft’s Edge browser, which, unsurprisingly, is still designed for Intel Macs. I do most of my day-to-day job within Edge, including accessing web-based apps like Slack, WordPress, Gmail and more. Of course, I could switch to the M1 version of Safari, but it would be a lot of work to shift everything over to Apple’s browser. While Edge runs decently through Rosetta 2, it does feel slightly sluggish at times, especially when launching apps like Slack and Gmail.

It’s also worth noting that restoring a new M1 Mac from a Time Machine backup is both time-consuming and somewhat frustrating. Following the restoration, the M1 MacBook Pro locked up several times. In fact, some Adobe CC apps wouldn’t even open initially until I restarted the computer. I’d suggest doing a clean install if you’re moving from an Intel to an M1-based Mac.

To be fair, these issues will start to disappear as more app developers port their software over to Apple’s M1 chips. The issue is it’s unclear how long that’s going to take.

The first M1 Macs

All three devices, including the MacBook Air, 13-inch MacBook Pro and the Mac mini, all look identical to their Intel counterparts.

Apple will almost certainly subtly change the design of all three devices since the architecture of the M1 probably gives it the ability to reconfigure the look of the Air and MacBook Pro. Unfortunately, that hasn’t happened yet.

The Mac mini looks the same as its Intel-based counterpart, and so does the MacBook Air. The M1 MacBook Pro, on the other hand, replaces the entry-level Pro that only features two USB-C Thunderbolt 3 ports.

The fact that the new M1 MacBook Pro only features two USB-C ports is strange and disappointing. Apple claims that it opted for two ports simply because the new M1 Pro replaces the two-port Intel variant. While true, it’s also likely a limitation of Apple’s M1 processor to some extent, or possibly related to its license to use Intel’s Thunderbolt technology.

This forced me to reconfigure my work from home setup considerably. First, my USB-C-to-USB-A hub needed to be moved to the laptop’s left side along with the USB-C cable I used to connect to my 32-inch 4K BenQ EW3280U monitor. Further, when both of these devices are connected, I’m unable to use my USB-C SD card reader, forcing me to use a USB-A SD card reader with my hub.

There’s also a power issue with my USB hub where as soon as I plug the USB-C card reader in, it disables the Logitech Unifying receiver. I realize that these issues are specific to me, but other people will likely experience similar problems if they plan to make the jump from a four USB-C port MacBook Pro to a two USB-C port M1 MacBook Pro.

Since the MacBook Air also only features two USB-C/Thunderbolt 3 ports, I experienced the same issues with Apple’s lightweight laptop.

While minor inconveniences in the grand scheme of things, in the era where many of us work from home, pain points like this are frustrating.

It’s also worth noting that all of Apple’s M1 devices can only be configured with 16GB of RAM, which seems to be a limitation of the M1’s architecture.

All M1 devices feature the same processor

The first thing to note about Apple’s first M1 Macs is that the MacBook Pro and the Mac mini are technically more powerful than the MacBook Air.

While all three new M1-powered Macs feature the same CPU and GPU and can theoretically run at identical speeds, the fact that the MacBook Pro and the Mac mini feature a fan, allows the computers to run at peak performance for longer. On the other hand, the MacBook Air doesn’t feature a fan and, as a result, features cooling that isn’t as efficient as Apple’s other two M1 launch computers.

Generally, modern CPUs run faster when they feature better cooling.

While I haven’t spent that much time with the new M1 Macs, this seems to be accurate based on the benchmarks (seen below) and my actual experience with the devices. For example, I connected the M1 13-inch MacBook Pro to my 4K monitor, opened Lightroom CC, Photoshop CC and edited several RAW images. On top of this, I played a 4K video from YouTube on my monitor and had several Edge windows running simultaneously.

While this would normally result in my 13-inch MacBook Pro (2020) with an Intel Core i5 processor and 16GB of RAM lagging quite a bit, the new M1 MacBook Pro’s fans didn’t turn on for several minutes and I didn’t experience any slowdown. I experienced similar results with the new M1 Mac mini, which also features a physical fan.

While things did run more smoothly with the new Air when compared to its Intel counterpart, there were instances where I’d be stuck with a spinning beach ball for several seconds, especially with Adobe’s software.

It’s important to note that all of this software is being emulated through Rosetta II. It will be interesting to see how the real-world performance changes once the apps I most frequently use get dedicated M1 versions.

Though battery life seems improved across all three devices, it isn’t easy to definitively know if Apple’s claims are accurate given I’m emulating software via Rosetta 2. On paper, Apple says the MacBook Air with M1 can get 15 hours of web browsing and 18 hours of Apple TV app movie playback (it’s unlikely most Mac users will only be watching video through the Apple TV app). The MacBook Pro, which features a larger 58.2Wh battery compared to the MacBook Air’s 49.9Wh, can get up to 17 hours of web browsing and 20 hours of Apple TV movie playback.

Battery life does seem improved across the board and in some ways, reminiscent of the classic Macbook Air from several years ago, though more testing is definitely necessary. I can say that I wrote most of this feature and edited photos for it with the M1 MacBook Air, and the battery still had 30 percent left after starting from nearly a full charge and working from roughly 11 noon to 6pm. This is very impressive and well beyond what the Intel MacBook Air is capable of.

One major question that still remains surrounding Apple’s new M1 Macs is when the tech giant plans to introduce GPUs that aren’t integrated into the M1 chip. Though it’s still unclear, the tech giant likely plans to do this with the 16-inch MacBook Pro with M1 when it inevitably appears likely in early 2021.

M1 benchmarks are impressive

Though benchmarks don’t always tell the full story when it comes to devices, and this is especially apparent with Apple’s new M1 Macs given nearly all apps are still emulated, they still show off what a true generational leap the M1 is when it comes to the future of Apple’s Mac line.

Across the board, the single-core and multi-core performance of the M1 is well beyond what I expected.

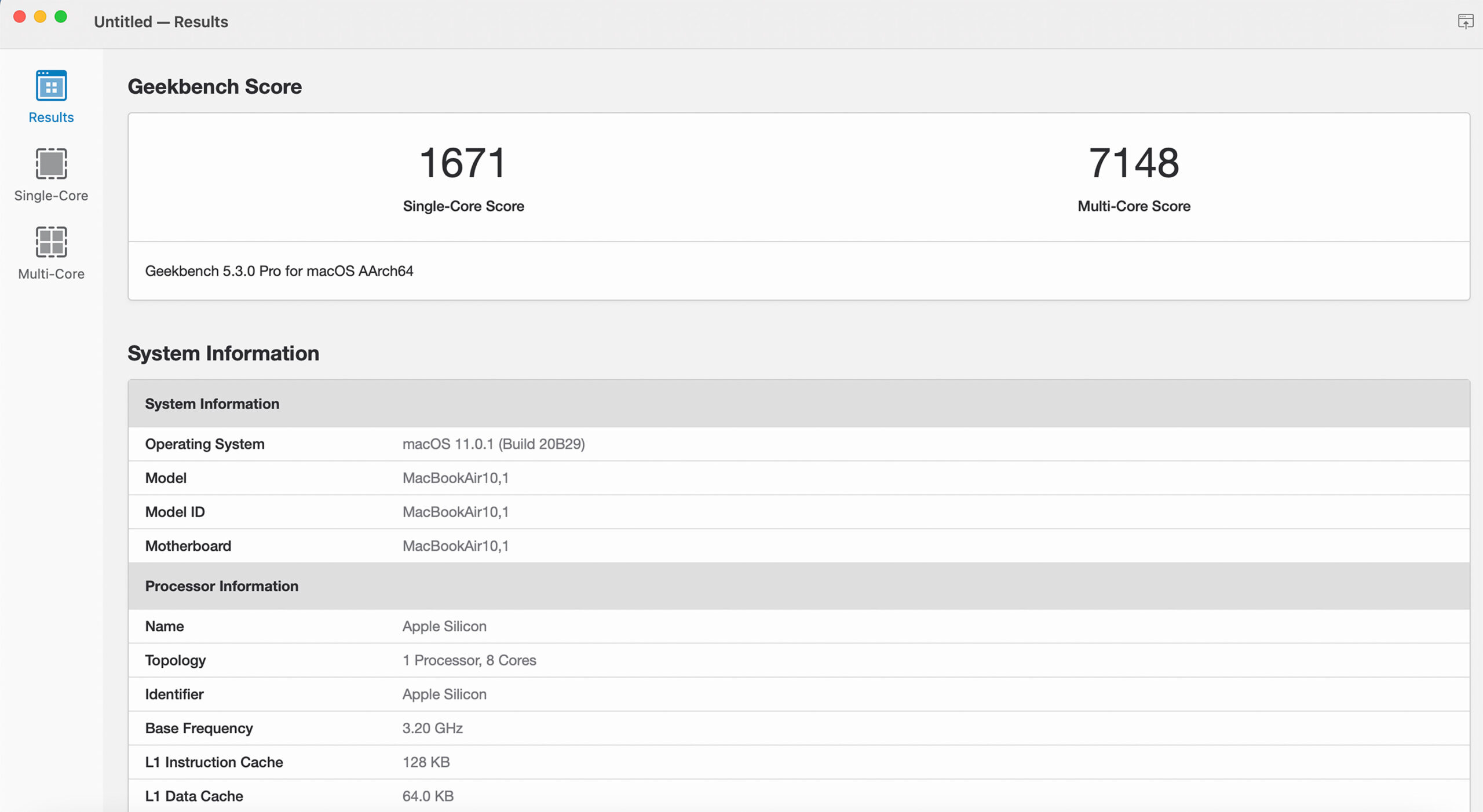

MacBook Air

The MacBook Air with M1 hits 1,671 for single-core and 7,148 for multi-core performance. This, shockingly, makes it more powerful than the 16-inch MacBook Pro (2019) with an Intel Core i9-9980HK processor in terms of multi-core performance, which comes in at 6,880.

Regarding single-core performance, the MacBook Air with an M1 chip comes in at 1,588, which is well above the Intel Core i5-1038NG7 13-inch MacBook Pro (2020) (1,147), the laptop I use every day.

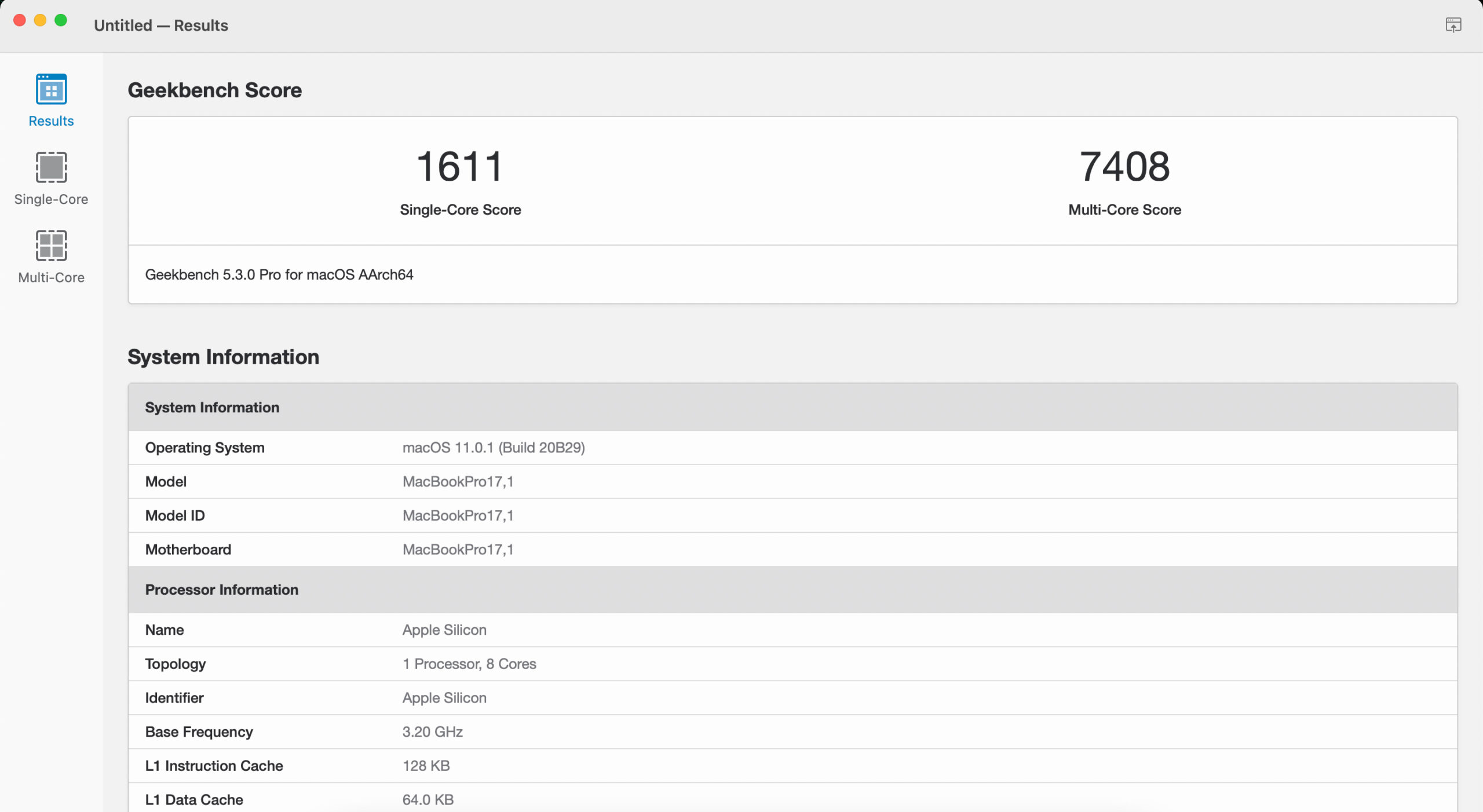

MacBook Pro

Apple’s 13-inch MacBook Pro with M1 hits 1,611 for its single-core score and 7,408 for its multi-core score.

In terms of multi-core performance, this is higher than the 6,880 the 16-inch MacBook Pro (2019) with an Intel Core i9-9980HK is capable of achieving and even surpasses the 27-inch iMac with an Intel Core i9-9900K processor (8,273).

This makes the laptop substantially more powerful than the Intel Core i5-1038NG7 13-inch MacBook Pro (2020) I use as my daily driver (1,147) and even the 27-inch iMac (2020) (1,248), in terms of single-core performance.

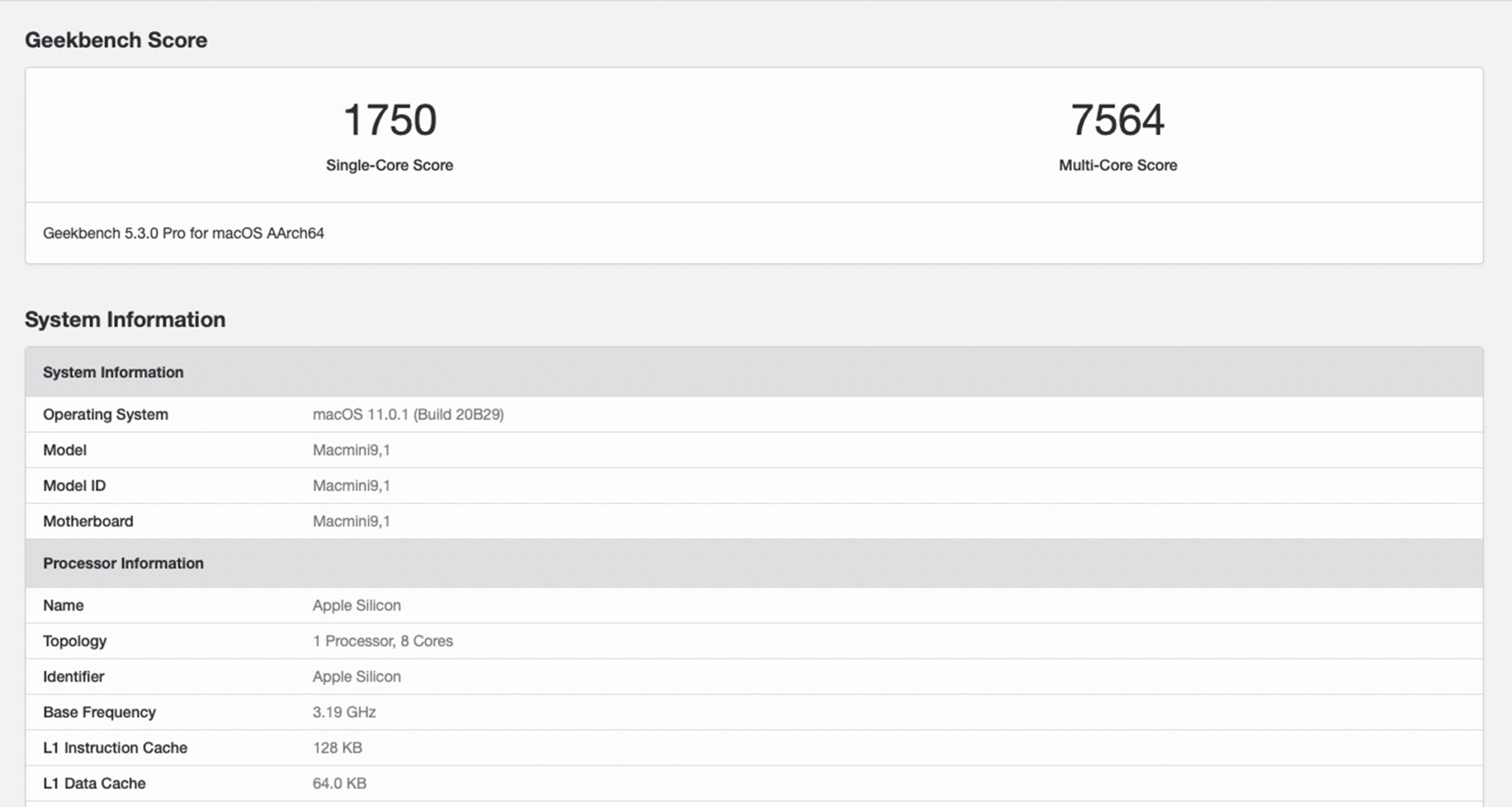

Mac mini

Finally, Apple’s M1 Mac mini hits 1.750 for single-core and 7,564 for its multi-core score. This puts it just below the 27-inch iMac (2019) with an Intel Core i9-9900k processor, which hits 8,273 for multi-core, but above the 16-inch MacBook Pro (2019) with an Intel Core i9-9980HK processor (7,989). It’s also way above the Mac mini (2018) with an Intel Core i7-8700B processor (5,495).

Similar to every other M1 device, this puts the Mac mini above the 27-inch iMac (2020)’s 1,248 single-core score and leagues ahead of the Mac mini (2018) with an Intel Core i7-8700B processor (1,102).

Should you buy an M1 Mac now?

The answer to this question is somewhat difficult. While the performance of Apple’s new M1 Mac line is undeniably impressive, Rosetta 2 emulation still needs work. This means that those who live in a world where they only use Apple’s own apps and services — and a lot of people do — the transition will be fine, and they’ll really appreciate the additional hardware power and battery life the M1 offers. For everyone else, it’s likely worth waiting until more third-party developers release M1 optimized apps.

In my particular case, Adobe’s CC suite is the missing link with the new M1 Macs. We know that Adobe’s most popular apps will likely get dedicated M1 versions, but it’s unknown when that will happen. MobileSyrup reached out to Adobe for more information regarding Creative Cloud’s release on M1 Macs and did not receive a response from the company.

Further, Microsoft releasing an M1 optimized version of its Edge browser would also help convince me to switch to an M1 Mac since moving between browsers is often a little tedious. Yes, I could switch to Safari, but I also work on Android and Windows devices, so this would ruin my ability to jump between platforms.

It’s also still unclear if Apple’s Universal App strategy that allows iOS and iPadOS apps to run on M1 Macs natively will pay off because they’re not yet widely available. While it will be great to see the macOS app ecosystem expand significantly, every touchscreen-based app likely won’t translate that well to mouse/trackpad input. That said, the introduction of mouse/trackpad compatibility on iPadOS will hopefully help make iPad apps translate better to macOS.

With all that said, it’s clear the M1 is the future of Apple’s Mac line — unfortunately, as expected, there’s just going to be growing pains for the next few months.

The new 13-inch MacBook Pro with M1 starts at $1699 for the 8GB of RAM, 256GB of storage iteration. Apple is still selling Intel-based versions of the MacBook Pro. The 8GB, 256GB of storage MacBook Air with M1 starts at $1,299. The M1 version of the Air replaces the Intel variant. Finally, The base-level M1 Mac mini now starts at $899 and ranges up to $2,149 if you add the 2TB hard drive and 16GB of RAM add-ons. Apple is still selling the 6-core Intel-based Mac mini for $1,399 CAD.

Update 23/11/2020: Some of the recovery issues I encountered might have had something to do with a macOS Big Sur authentication error that caused issues with launching and installing apps across all MacBooks shortly after the OS update’s launch.

Update 18/11/2020: Google Chrome for Apple’s new M1-powered Macs is now available.

Update 17/11/2020 5:20pm: A limited beta version of Photoshop CC designed for Apple’s new M1 chip is now available.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.