Stéphanie Marchand didn’t always plan on being a game developer.

“I wanted to be an astrophysicist,” the Behaviour Interactive vice president of production admits, citing a love for math and science. But it didn’t quite turn out that way.

“People [who knew] me very well realized that I have a very results-oriented and not very patient personality and were reorienting me towards engineering, instead of scientific or academic research, which would [better] fit my personality,” she says.

While Marchand notes this was initially disappointing, she soon realized this opened up another door: computer engineering. Around this same time, the likes of Ubisoft and Behaviour began moving into Montreal, showing the Quebec native that she could break into the gaming industry here at home. Now, Quebec is one of the biggest game development hubs in the world. In other words, she could capitalize on a lifelong love of video games.

“I realized with about two years left [of school] that actually, I could be doing video games. So I started to reorient all my studies towards gaming because there was no video game-specific specialty in computer engineering in Montreal. So I started to pick up classes, like ‘oh, I’m going to need like artificial intelligence, and maybe like computer vision, computer graphics…’ So I was cherry-picking those classes.”

Moving on up

Her efforts definitely paid off. She’s now been in the industry for nearly two decades — the majority of that time at Behaviour, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. At the studio, Marchand’s held many titles, including programmer, lead engineer, producer and executive producer. While Behaviour is best known today as the studio behind the massively popular multiplayer game Dead by Daylight (DBD), it has a storied history that includes game production for the likes of Disney (various Kim Possible titles), Sega (Iron Man), Bethesda (Fallout Shelter) and Warner Bros. (Game of Thrones: Beyond the Wall). Marchand herself has taken part in more than 45 game development cycles at Behaviour.

Marchand credits her time at Polytechnique Montréal for preparing her for all of the jobs she’s had at Behaviour. Specifically, she says she gained experience through involvement in various committees, serving as president of the students’ board, organizing shows and parties and helping students get internships at companies. That would all prove invaluable once she

eventually joined the industry.

“When I started in games, I really loved programming, but I realized, it wasn’t that organized around here. The lead programmer back then used to be the most experienced and best programmer on the team. But that was weird because he was also supposed to give us what we should be working on next, but he was always super busy with the toughest kind of work — he was the bottleneck, basically, of the team. So I started talking to everybody and just being myself — talking to the artists, talking to the producers, and organically starting to organize the team. I was not necessarily the best programmer on the team, but I was definitely the best organized.”

This helped her be promoted to lead programmer, a position she would hold for three years on titles like Disney’s Kim Possible: What’s the Switch?

“But then I realized ‘producer’ is really what I wanted to do because you’re the maestro — you’re really in charge, you see all the moving parts. And I’m like, ‘yeah, with my background in computer and engineering, my background in programming,

I could definitely understand how things are working better. So I started to move towards becoming a producer.”

While she says she had “a lot of fun” as a producer, she became really attracted to operations.

“So, assigning the right people to the right paths and eventually assigning the right people to the right projects — I see all those things as puzzles in my brain– getting all of that working in training future producers. In my current role, we also work with external partners, and we are producing games for others, like Ubisoft and Microsoft. So there’s a lot of partnerships, clients and providers relationships to manage, and I love doing that.”

And there’s quite a lot to manage, indeed. Per Marchand, Behaviour’s total workforce sits at around 900 — up nearly 300 from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic alone. Of that 900, about 200 are currently working on Dead by Daylight, which surpassed 36 million players in 2021 since launching in 2016. Behaviour has also gotten to play around with high-profile DBD crossovers featuring the likes of Halloween (Universal), Saw (Lionsgate), Stranger Things (Netflix), Resident Evil (Capcom) and Silent Hill (Konami).

According to Marchand, the longevity of DBD can be attributed to the “passion” of the core development team, who originally worked on the 2010 action-adventure game Naughty Bear.

“I worked as the lead programmer on the first [Naughty Bear] for a short period of time, but I was not, back then, a big horror game fan. So being really in the trenches, and creating the game was a bit less for me. But I can tell the passion was there,” she says. “A lot of people were absolutely passionate about this genre, about creating something new.”

She says the DBD team being a sort of “internal community” within the larger Behaviour also proves beneficial to developers.

“There’s also a possibility for people to go in and out of the project. Because it’s two years of production, six years of life, eight years — that’s a very long time. So people have been on this project for eight years, and they’re still absolutely passionate about it. Some people just join. Other people left for a while, had a taste of something different, [then] came back. So I think that’s a very important element inside the company.”

She attributes Behaviour’s history of partnering with other companies as a key contributor to how it continuously lands these major DBD pop-culture crossovers.

“We’ve been known to translate brands into games, even when it’s a brand that’s already [in] a game,” she says, citing the mobile title Assassin’s Creed Rebellion for Ubisoft. “So we are renowned for it. That’s why it allows us to integrate those DLCs containing the big known licenses and IPs into this game with great success.”

Of course, DBD is only one part of Behaviour; that leaves around 700 other people at the company to work on all sorts of other projects. This includes Activision’s Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 1+2 HD and Call of Duty Vanguard, PlayStation’s Days Gone and, from fellow Canadian teams, Xbox’s Gears 5 (Vancouver’s The Coalition) and Ubisoft’s Rainbow Six Extraction (Ubisoft Montreal).

“I was not necessarily the best programmer on the team, but I was definitely the best organized.”

While that sounds like a lot to balance, Marchand says Behaviour as a whole is broken down into many smaller divisions. “Our teams are not large — Dead by Daylight is, by far, the largest we’ve ever had. But usually, when we’re in development, we would need between 30 and 50. So everybody can contribute, and we encourage everybody to contribute. If anybody has an idea, you can go up to creative directors and designers and talk about it. And if it’s sound, it’s going to be considered.”

Bringing in diverse talent

For Marchand, a major focus of her current job lies in fostering “the next generation of leaders” in the gaming industry. “That’s something I really care about.” She says this is especially important considering how “quickly” Montreal’s gaming sector continues to expand.

“Yes, we all want senior people that have years and years of experience. But Montreal adapted — we have video game programs all over the province currently, and they are producing great juniors and great interns. We need to make sure we have a way to get them in and train them and move them up the ranks so they can become seniors and eventually train more juniors,” she explains. “We realized that years ago, as a company, we really foster a relationship with all of the schools, getting interns, getting juniors in. We really care about training them and we don’t expect them to learn everything in school.”

This includes giving them “buddies” to shadow for their first three months, specific annual training and focusing on development trends surrounding engines like Unity and Unreal. All of this, she says, will help them realize their potential.

“I think everybody can learn to be a good manager. Following tasks and learning how tools work is not that complicated. But to become a leader and inspire people? That’s harder. And as we want to be really oriented towards people and less those tasks, and really give people objectives and goals, then we need managers that are leaders that understand this and make this shift. So this is something I’m more involved in.”

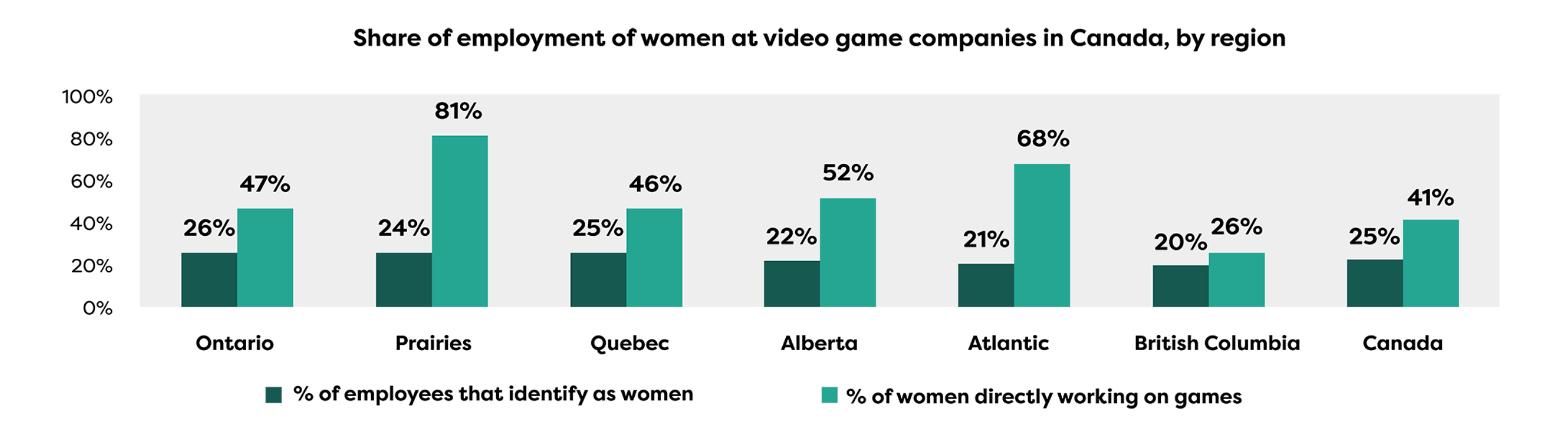

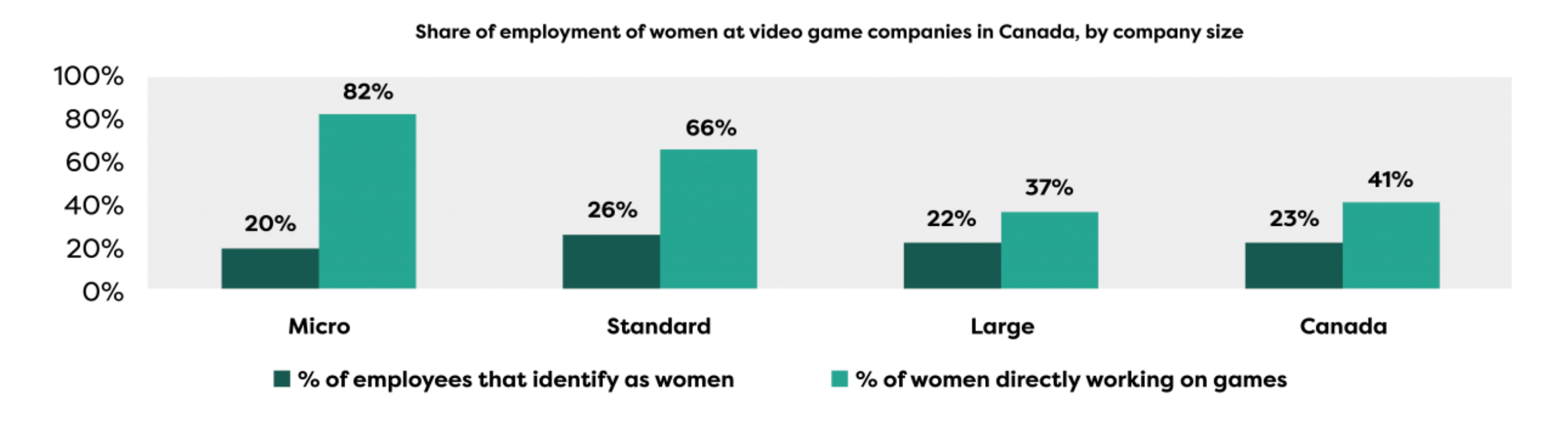

Women, specifically, are a group she aims to bring more of into the industry. According to the Entertainment Software Association of Canada’s Canadian Video Game Industry report for 2021, only 23 percent of Canadian game developers are women. Marchand says there are many ways to address this at various levels, starting by drawing from her own experiences.

“When you become a leader in a world that doesn’t have a lot of women around, it could be interesting, and there could be challenges — they’re different for everyone. Because I studied science, and I went to engineering, I’m used to being in an environment that’s very male-dominated,” she says.

“But we have other women that come from other worlds with different codes, and they need to learn how to be a leader in the video game world. So this is where I try to adapt and explain what I went through and use my experience as much as possible, but also understand where they’re coming from and lead them. It’s great because I can use my experience, but I can use that to coach men as well. Some of my best coaches are men, so I think that’s fine. But it’s really just to understand this little difference.”

“We need to realize that our hiring systems and the way we hire people has been done by men for men, and there’s bias in there that we don’t really realize.”

Part of preparing them, she says, is to be aware of, and try to combat, the types of discrimination that women can face. While she says she’s never personally experienced this at Behaviour itself, that wasn’t the case when she first travelled to the U.S. to meet partners and clients.

“They’d look at my hands and say ‘you’re not married, hmm, alright.’ I was like, ‘I’m [from] Quebec, people don’t really get married [here].’ And they were like, ‘okay,’ and they were asking some questions. And I look a bit younger than what I am for my age, and I think that they were often surprised. We spoke on the phone — we weren’t doing a lot of video conference back then. But when they meet me in person, they’re like, ‘Oh, how old are you again?’ I look about 10 years younger than I am. And so they think, ‘why is this 25-year-old girl [here]?’ I’m 35.”

These kinds of exchanges have since informed how she speaks with aspiring women game developers in her current job.

“So I realized, ‘how do I bring in a conversation early my experience, my age and things [like that]?’ I’m trying to give that information and speak to other girls about what I’ve lived through so they’re not surprised and they are mentally equipped to go through it. I feel as well that the world has changed. That was about 10 to 15 years ago — I think it’s better today, but it might not be exactly one-to-one yet.”

She also calls on the industry at large to acknowledge “that there’s a problem” when it comes to the number of women it employs. “When I was in computer engineering, there were 12 percent women, and we’re talking 20 years ago. And I checked the numbers recently, and it’s still 12. When I was there, the belief was that it was going to grow because it hadn’t grown the year before […] But it actually stalled at 12.”

According to a Government of Canada report, a common reason women don’t pursue STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education in post-secondary is that they lose interest. This has been attributed to feelings of isolation in STEM classes and lower academic self-confidence than men of equal academic ability, among other causes.

For Marchand, it’s important to encourage STEM in a girl’s formative years, as it can make all the difference.

“Try to work with the schools and see how we [the gaming industry] can — even at the kindergarten level and such — get just a little bit more programming and a bit more like science in general towards women. I think that could go a long way as well. Because you are going to make choices in high school that are going to kind of disqualify you from studying science later in life, which will close the door for programming. Of course, you can still be a designer and an artist, but one of the three main branches is now closed to you. So that’s something we have to be mindful of.”

She adds that families can also play a key role in all of this.

“It’s [about] families explaining how important it is to give the opportunity to younger girls to do experiments. I used to do physics experiments in my kitchen when I was a kid, and my mother would buy me experimental books and I love that. My father, being a computer engineer himself, would give me little programs on the weekends. I spent my life around computers, so for me, I never saw them as threatening, or, ‘it’s for men in the basement,’ or anything [like that].”

“I think the more women you get, the more you attract, because then you’re getting outside of that stigma of ‘it’s a white man industry.'”

To that point, she notes the general perception of games is something the industry itself can help improve. In the past year alone, several stories have come out about toxic work cultures at the likes of Activision and Ubisoft, specifically alleging mistreatment of women. The subject of crunch — excessive and prolonged overtime — at many studios also comes up. Behaviour, to its credit, has a strong reputation in the industry, having a crunch-free culture and being named one of Canada’s Best Places to Work in 2021 by GamesIndustry.biz and Top Montreal Employer and Best Workplace for Hybrid Work by the Great Place to Work Institute in 2022. But the industry’s larger image could use work, Marchand admits.

“Video games have something of a bad rap with everything that we see in the news, and I think [the industry] needs to make amends for this,” she says. “Every company needs to speak up more and say, ‘this is the past, and here’s how we’ve addressed it.’ To kind of reconfirm and win back the confidence of women that this is an industry where they can flourish — I think that’s very important.”

Hiring practices are also an area of improvement, she says. “We need to realize that our hiring systems and the way we hire people has been done by men for men, and there’s bias in there that we don’t really realize.”

As an example, she mentions how the gaming industry typically advertises for higher positions than the actual role that needs to be filled.

“Let’s say I want to hire an intermediate programmer. I’m going to advertise for [a] senior programmer, knowing that a lot of people are going to apply but don’t exactly have the qualifications. So hopefully, I can get somebody at the previous level. But women are not going to apply. They’re not going to apply if they don’t believe they tick all the boxes. It’s proven research — it’s known. The industry is still using this paradigm when hiring, so it’s disqualifying women from the process because they’re going to disqualify themselves.”

To help with that, Marchand says the industry should start by bringing in women for all kinds of roles, which, in turn, will open up more technical opportunities like programming.

“A lot of influencers, managers and all those new roles — what we’re seeing is [they’re] attracting a lot more women. So even if I’m not going to get more women programmers tomorrow, maybe in other disciplines I have a chance to start to get more women in the company. I think the more women you get, the more you attract because then you’re getting outside of that stigma of ‘it’s a white man industry.'”

These are all changes that can be made now and over the next few years, but looking even further ahead, she says another aspect that can make a “big difference” is the social element of games.

“When I spoke to girls in high school and tried to understand if they wanted to go in video games, they’re like ‘no, I prefer to chat with my friends or have more social activities.’ But right now, there’s a lot of games that have guilds and chat systems and you’re collectively trying to win — you’re not necessarily just fighting each other. I think that will make it more appealing to girls. We’re seeing a lot more [apps] like TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram — those types of software — starting to mingle with games, and see where that brings us in the future. I think that will be an eyeopener.”

Ultimately, though, Marchand hopes stories like hers will help encourage more women to get into gaming.

“For a lot of girls, the fact that I went from programmer to vice president at Behaviour makes them trust that Behaviour will promote and help women because I’ve done it in this company. So it’s like, ‘she’s done it.'” she says. “I’ve paved the way. And other people could do it — there were others before me but they’re not with us anymore. I hope I can inspire other girls to kind of go up the rank and pick up leadership positions.”

This interview has been edited for language and clarity. For more information on International Women’s Day in Canada, click here. Some women in gaming initiatives you can learn more about and support include Paidia, the*gameHERs, Women in Games International, She Plays Games, Femme Gaming, Pixelles, Girls Who Code and Girls Make Games.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.