Welcome to Tête-à-Tête, a series where two of our writers converse on interesting topics in the mobile landscape — through chat. Think of it as a podcast for readers.

This week, Daniel and Douglas talk out their feelings on music ownership.

Douglas Soltys: Dearest Daniel, while perusing the latest print edition of the Mobile Times Herald, I ran across the most interesting piece of news: Spotify has launched in Canada. I was flabbergasted to learn that this ‘streaming music service’ is how the youth of today consume their favourite ballads, folk songs, and big band numbers.

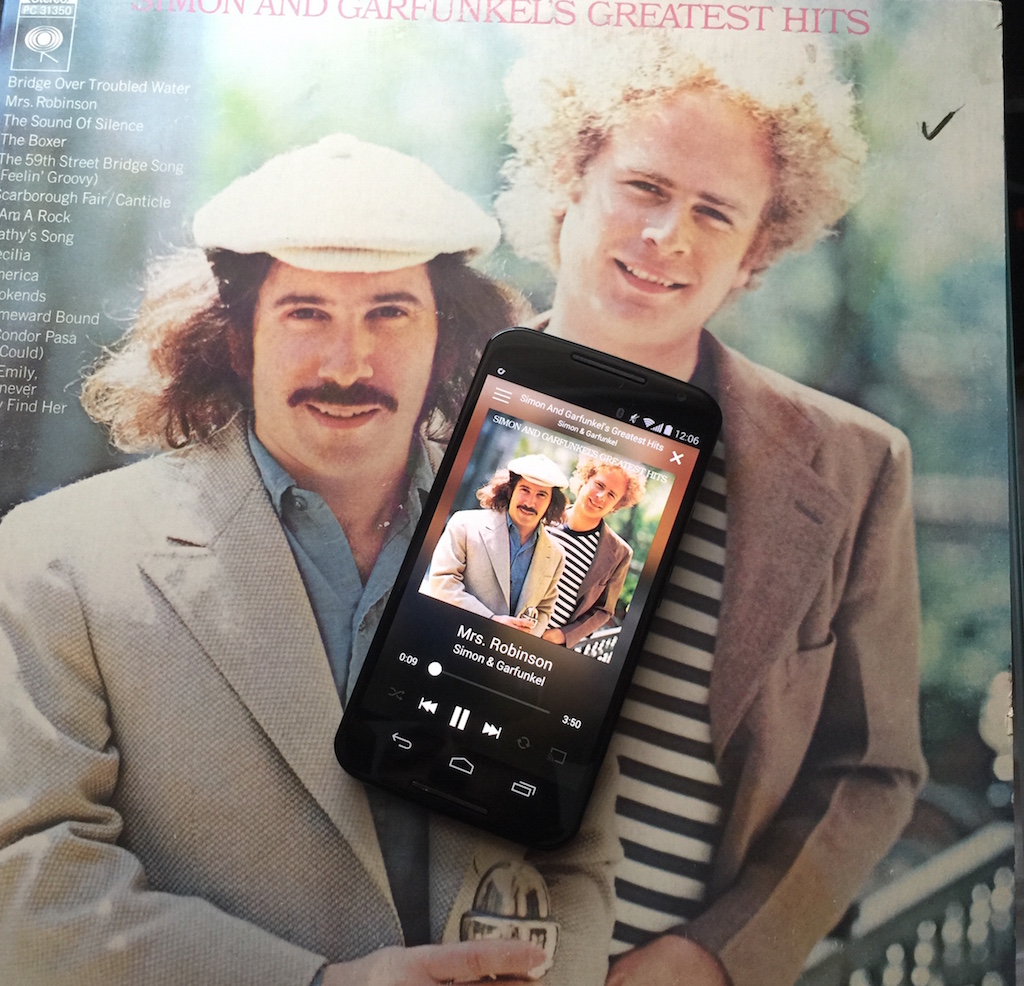

Now, I may be old-fashioned, but I still buy my music on vinyl. I then take the old-fashioned URL provided in my vinyl album, and download the music digitally into my iTunes. Why? because I like owning my music, I like having a library of music on hand at all times, and I don’t like the idea of paying someone a monthly fee for a service you can get free by turning on the radio.

Now Daniel, do you stream? Is that what the kids are calling it? Is it dangerous?

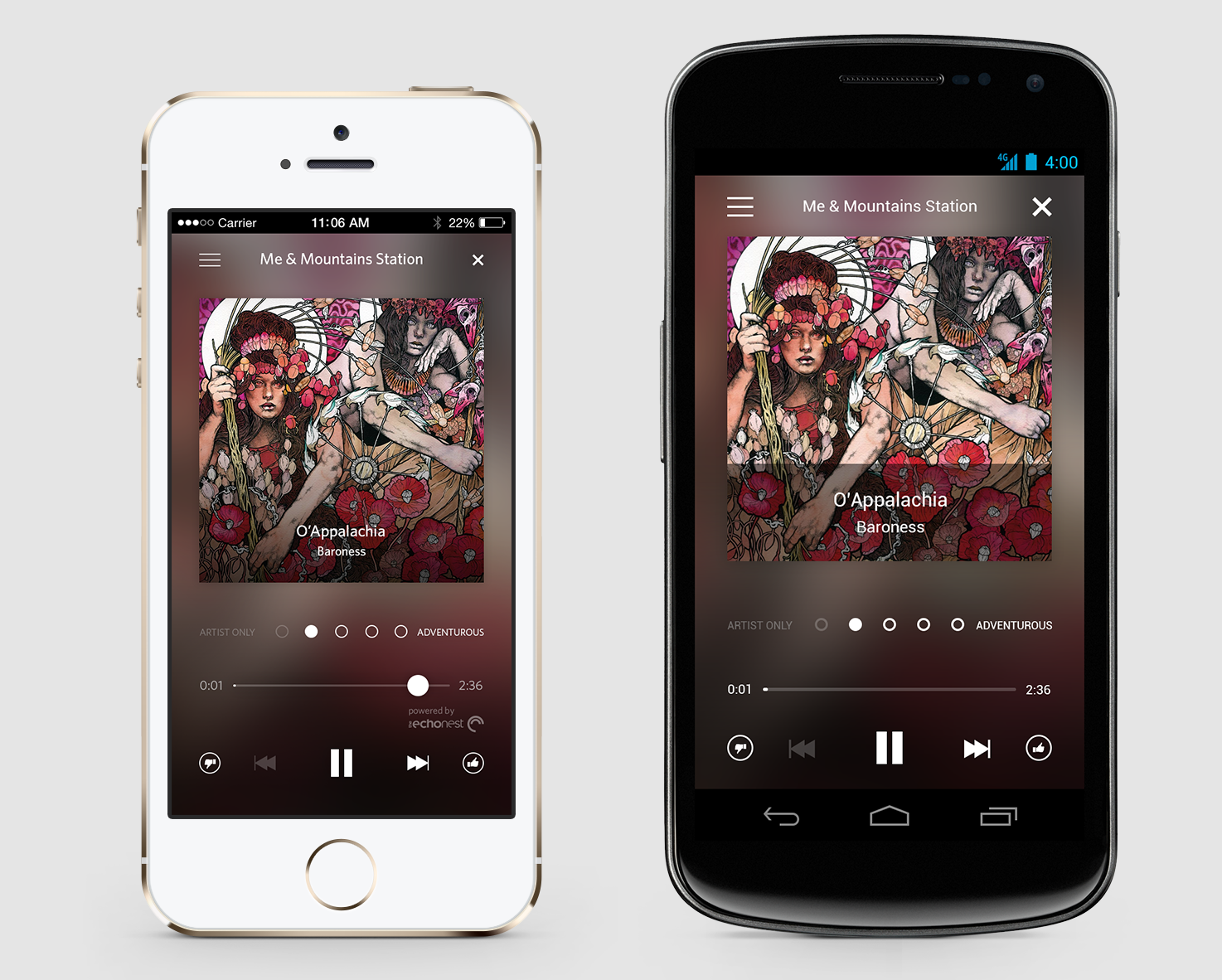

Daniel Bader: Douglas, I stream. In fact, the last CD I bought was in 2012, and it was an album released in 2002 (Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, if you must know). I have purchased individual songs on 7Digital, but since Rdio came to Canada my hands have been freed from the tyranny of stuff.

More than ever, I reject things. My shoebox apartment demands that I purge anything that resembles detritus (which, as a review of consumer products, is quite difficult) so phone boxes, CD cases — even books — have been digitized.

On the one hand, I do miss the process of opening a jewel case and hearing the whirr of the motor, but not enough to want to own every piece of music I enjoy from time to time. Streaming has completely changed the way I listen to music: it allows me to create playlists of my favourite songs from a single band, or genre or decade. It enables rediscovery of old favourites and new artists that I may be interested in. Rdio, over the years, has learned what I like and when an album ends it begins playing tracks it knows I’ll enjoy despite knowing nothing about the artist.

So yes, I stream. And for $9.99/month I’ve overcome my need to own that music. How could you possibly think that’s a bad thing?

Douglas Soltys: Because, dear Daniel, while you are concerned with getting rid of things, I am concerned with loss. Or more specifically, the music that I pay to have access to no longer being accessible. We’ve seen this sort of thing with streaming video services like Netflix — one day all four seasons of Battlestar Galactica are there, the next day they’re not. While I have yet to hear of similar content disruptions with streaming music services (it wouldn’t matter anyway, as none of them run on my gramophone’s operating system), the threat is the same: that which you do not own can most easily be taken from you.

I’m also concerned about how streaming services affect one of the most important aspects of music: discovery. Uncovering new musical favourites previously took effort – a trip to the local store, perusal through the isles, the right recommendation from the bespectacled employee behind the counter. Having all content sent to us through our phones lowers the friction to discovery, but it also shortens its horizon. The core argument is very similar to the one you dealt with regarding predictive text on The Current this past week. Rdio might be smart enough to learn what you like and recommend things that sound similar, or music that other people also listen to, but it will never send something your way on the off chance it might crack you upside the head and change your life.

I also wonder how comfortable should we be with the free data about our personal tastes and preferences we give up for these streaming services. We already have worry about hacks and back-door government portals into our personal data, so why should we be so eager to tell marketers exactly the type of entertainment we consume? So they can continue to sell us more of it, at the expense of squeezing out anything that doesn’t beat-match the previous track?

Daniel: So you’re saying the scale of discovery is more subdued because Rdio and its ilk have a vested interest in pushing certain songs, perhaps being paid by the labels they rely upon for access to the music in the first place?

I don’t mind not owning the music because I rarely need to listen to a certain band or song; if one song isn’t available, I’ll find something that hits the spot. That’s the beauty of music: there are so many ways to arrive at the same feeling. If all we’re concerned about is ownership, labels would have suppressed incredible mashup acts like The Hood Internet and Girl Talk, and prevented us, as consumers, from hearing it.

I feel like streaming arrives at the best compromise between physical ownership and digital accessibility. While you’re paying a monthly fee to access someone else’s content, as long as that business is still viable access remains certain. As for disappearing artists or tracks, competition often leads to more popular artists going to the service with the highest bidder. Spotify or Google Play Music may have a few artists that Rdio doesn’t, but if I need to listen to Beirut I use YouTube or Soundcloud. Or I’ll buy the album.

I think that ownership needs to be rethought not as a poster on a wall, but access to the feelings that poster evokes. I don’t have that nostalgic connection to a record player, nor do I appreciate the “warmer” sound of the needle over the wax. To my ears, music sounds best when I want it, and Rdio, Spotify, Play Music and its competitors make that extremely easy.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.