At the risk of sounding like a broken record, it’s no coincidence the iPhone is often said to have the best smartphone camera on the market. Those advantages don’t come from optics alone, though Apple pours resources into that, too, but from a three-pronged approach takes developers just as seriously as it does sensors.

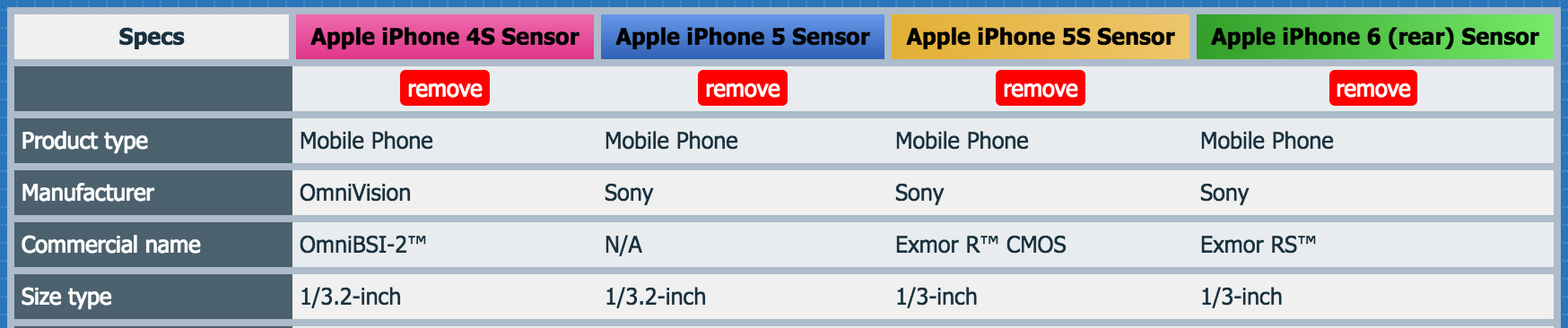

In truth, there is nothing remarkable about the sensor inside the iPhone. While custom-made, at first by OmniVision and, from the iPhone 5 onwards, Sony, the actual innards are no different than those found inside the average Galaxy or Xperia. Apple has just been smarter about processing, eking a better photo in more situations — thanks to software.

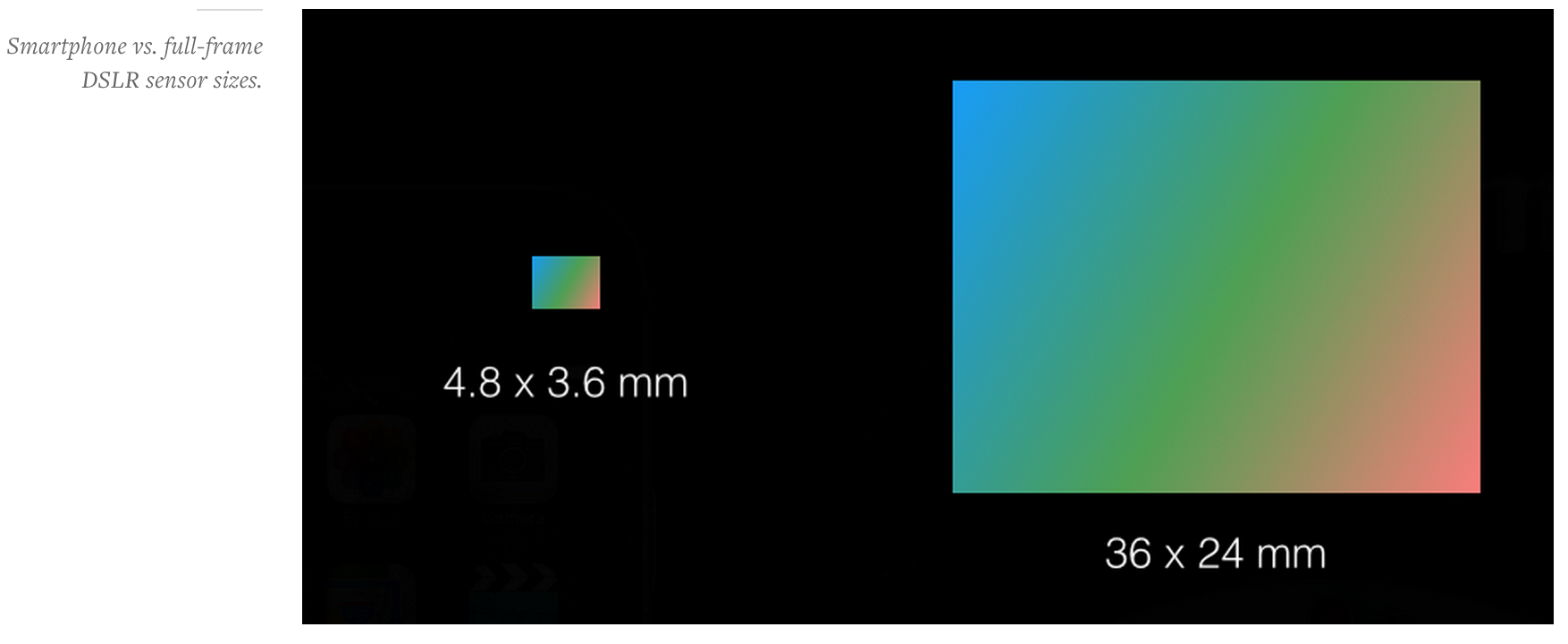

In recent years, Android and Windows Phone have improved in this regard, too, giving developers greater access to the more granular aspects of a smartphone’s camera. Sensors have improved, too, but are physically limited by the ever-decreasing thickness of the average high-end smartphone. It’s great that Samsung, Sony and LG can claim to have the highest-resolution cameras on the market, but when the sensor itself isn’t getting larger, they’re forced to cram more pixels into the same amount of space. This means less light can enter each pixel at once, leading to innovation in other areas, namely optical images stabilization and alternative backlight technologies like Samsung’s ISOCELL.

The next generation of smartphone sensors, however, need to be smarter, not just higher-resolution. There’s a reason Apple has kept the iPhone at 8 megapixels since the 4S: it’s been forced to make considerations for chassis thickness (they’re getting thinner every two years) as well as sensor size (which is increased marginally). As a result, the individual pixels have increased to around 1.5um, a number right in the middle of the LG G3 (1.1um) and HTC One M8 (2um).

There is nothing remarkable about the sensor inside the iPhone

In practice, this doesn’t mean a whole lot except that some phones should be marginally better at capturing low-light photos than others. The LG G3, like the Samsung Galaxy Note 4 and Nexus 6, employs optical image stabilization to help those small pixels stay active longer, so as to let in more light, without blur. The HTC One M8, on the other hand, uses a sensor big enough to capture more light in less time.

There are tradeoffs to both strategies, as there always are with hardware. That’s where software comes in. Google has done its part to improve the photo-taking experience in Lollipop with a new Camera2 API — the link that connects the hardware to third-party apps — and it’s a great start. Developers are now beginning to take advantage of the finer level of control afforded to them by the new API, from manual focus to shutter control, but the offerings are few and far between.

HTC took it upon itself to build a great custom camera framework for its smartphones long before Google released Android 5.0. The One M7 and M8 eked every bit of performance from its low-resolution UltraPixel sensor thanks to the work of its software engineers.

Nokia, and now Microsoft, has done a tremendous job with its own camera software, offering a keenly simple workflow that can be expanded with simple granular controls.

Similarly, in the last version of iOS, Apple kept its own camera app super simple and lets developers have as much leeway as they want. This has resulted in a bevy of successful premium apps specializing in bringing DSLR-like features to the handheld.

One example in particular caught my eye (and became the impetus for this piece). Hydra, a newly-released app from startup Creaceed, wants to work within the limitations of the iPhone’s small sensor. With a mandate to produce better HDR (high dynamic range) and lowlight photos, Hydra employs a strategy only recently available to devices: multi-shot processing. Because modern smartphones have incredibly powerful processors that can do stitching in real time, Hydra takes dozens of shots and, using the magic of algorithms, produces incredibly detailed, vibrant or well-lit photos, depending on the intended outcome.

These are features that OEMs will need to build into their native camera apps if they want to continue improving on the physical limitations of their devices’ camera sensors. Most people don’t want to mess with manual focus or to decide whether HDR should be activated. They just want things to work.

Camera performance continues to be a major differentiator between OEMs, and the companies like HTC and Apple that don’t manufacture their own sensors will need to continue to work on finding other ways to optimize output. Apple controls the rest of the stack, from the image signal processor to the API and operating system, while HTC modifies Qualcomm’s ever-improving ISP to do some really interesting things with its own camera framework.

The takeaway is that you don’t need higher megapixels to take better photos; your smartphone just needs to use its pixels more efficiently.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.